Last update: December 5, 2023

Introduction

To understand the historiography of the chapei, it is necessary to widen the geographical area of research from Cambodia to the Middle East, passing India, China and especially Thailand which offers an iconographic panel not found in Cambodia.

Sounds of Angkor has developed a complete website dedicated to the chapei lute. To access it for free, click here.

Origin of the word chapei

The word chapei (also transliterated chapey) derives from the Sanskrit kacchap(î), a term which designates a lute from ancient India. Kacchap(î) is also the source of the name of the equivalent of the Thai chapei, namely kracchapi, krachappi or grajabpi (กระจับปี่). The term kacchap(î) derives from the Sanskrit kacchapa, literally ‘turtle’. It may be hypothesized that the original lute's resonance case was made of a turtle shell. We find this type of instrument in the hands of traditional musicians. A large number of instruments around the world have names derived from Sanskrit, whether in Asia, Europe or West Africa. Some instruments have traveled for centuries maintaining their original root. By passing from one country to another, from one culture to another, from one musician to another, the instrument is adopted with its name, which undergoes variations related to the understanding of the word and to the speaker's ability to rephrase it. It is thus possible to trace the course of certain musical instruments through space and time thanks to their only name.

In West Java (Indonesia), also known as ‘Sunda’, the term kacapi refers to a plucked zither. In Sulawesi, kacapi designates the kakapi kajang lute also called kacaping.

The different names of the chapei dang veng

In Cambodia, the chapei is known under various denominations according to the mediums. This is not exceptional. Indeed, we find, throughout the world, names used by the people of the environment (amateur or professional musicians), by neophytes and also slang, imaged or scoffers names. Sometimes an instrument is named from its function or the function of the one it replaces. Some names extol the nationalistic fiber, like the Cambodian tro Khmer, while this instrument is not a Khmer creation, but an assimilation.

Thus, the chapei is known, in the milieu of the musicians under the shortest term ‘chapei’, or chapei veng and now officially chapei dang veng (long-necked chapei) since its classification by UNESCO. The term chapei veng or chapei dang veng ចាប៉ី ដង វែង —also written chapei(y) dong veng— allowed, a few decades ago, to distinguish it from a small derivative lute, the chapei touch or chapei dang klei, which was created in the twentieth century. It had a shorter handle, but it has now disappeared.

The term pin derived both from the old Khmer word vīṇa, which used to refer to the harp and to the Sanskrit one vīṇā, which named the ancient stick zithers. By extension, pin became in Cambodia the generic name of all plucked string instruments: chapei, ksae diev or ksae muoy, takhê. Phin (Thai: พิณ, pronounce [pʰīn]) is a lute with a pyriform sound box, originally from the Isan region of Thailand and played mainly by Laotian ethnic groups in Thailand and Laos.

Western classification

Western organology defines chapei as a long necked lute. It is joined by its most common Khmer denomination ‘chapei dang veng’ meaning literally ‘long necked chapei lute’. It is equipped with a variable number of high frets.

The chapei, between myth and reality

It is a tenacious myth that should be swept in one stroke. It is said that a representation of chapei exists among the bas-reliefs of the Angkor Wat temple. After surveying this temple for 20 years and scanning each square inch, we can say that there is no representation of chapei in Angkor Wat. There are also, to our knowledge, no lute representation during the pre-Angkorian and Angkorian periods in Cambodia. On the other hand, it exists in the 8th and 9th centuries among the Chams of Vietnam, in Siam and in Borobudur (Java - Indonesia). But they look nothing like chapei. Everything has more, a chapei player is represented from behind on one of the walls of the south pagoda of Angkor Wat site!

However, the lack of representation of lutes on pre-Angkorian and Angkorian bas-reliefs doesn't mean that they didn't exist at these times. Remember that the bas-reliefs show musical instruments of Indian origin and include mythological scenes, martial, palatine, and religious. Some of these instruments disappeared with the development of Theravadin Buddhism and then with the collapse of the Khmer Empire. But it goes without saying that, alongside music of royal tradition, indigenous art flourished among the population, drawing its sources from the old Mon-Khmer culture, whose music was probably based on bamboo percussion, aerophones and chordophones. we can still find among the mountain populations bordering borders of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

When did the chapei arrive in Cambodia?

We currently have no source attesting to the arrival of the chapei in Cambodia. Thailand, on the other hand, can certainly be traced back to the 18th century. See below the chapter "Iconography of kracchapi in Thailand".

Geographical origin of the chapei

The following considerations are not conclusive, but are a reflection on possible tracks. Everyone is free to make comments, as long as they are documented!

What is remarkable is the association, both in Cambodia and in Thailand, of several instruments within the same orchestra: the chapei, the pei ar oboe, the tro Khmer fiddle and the drums skor arak or skor daey.

In terms of documentation, we have various iconographic sources: engravings of Louis Delaporte (late 19th and early 20th centuries), photographs and postcards from the early 20th century, the paintings of the Silver Pagoda at the Royal Palace of Phnom Penh and pagodas that survived the Khmer Rouge revolution. In Thailand, there is a very rich iconography.

Two instruments arouse our attention: the tro Khmer and the pei ar. The first one is a trichord fiddle known in Java (Indonesia) or in Malaysia. In the Javanese and Malaysian fiddle, the tro Khmer borrows the triangular shape of the soundbox. We know that the Javanese fiddle was introduced by the Muslims. As for pei ar, we know such an instrument, with its wide reed, in Iran, Turkey and Armenia.

Let's look now at the names of these instruments. The term tro Khmer doesn't give us any information about where it came from. The tro sau fiddle came from China at an unknown time; so the term tro khmer was probably chosen to distinguish the instrument of the tro of Chinese origin.. In Thailand, the instrument equivalent to the tro Khmer is called saw sam sai (ซอ สาม สาย), and in Java and Malaysia, rebab.

The term pei could be derived from Persian ney meaning ‘reed’, material in which is made the reed of the pei ar.

The goblet drum already existed in the Angkorian era. It appears from the 12th century on the bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat. But it is not impossible that it was reintroduced at the same time as the other three instruments. Thus, the four instruments would have come with the Muslims. But the fact remains that the origin of the word chapei is Sanskrit.

The tracks' research of the chapei's origins

What are the clues to defining the origins of an instrument?

- Its full name or the root of its name are valuable informants on the provenance. But sometimes, this name goes back several centuries, even several millennia.

- The shape and materials can tell us about the basins of influence or the direct provenance.

- Technology.

We will try to study three tracks of influence:

- The Middle East track

- The Indian track

- The Chinese track

The Middle East track

The Middle Eastern track of the origin of the chapei is tempting because this instrument, in the same way as the Thai kacchapi, played until the Khmer Rouge revolution in formation with the tro Khmer and the pei ar which are Middle Eastern instruments. They could have arrived together, the current chapei being only an evolution of another original lute. The oriental lute whose soundbox shape is closest to that of the chapei is the tanbur. In Turkey, miniatures of the Topkapi Palace attests to the 16th century. On the other hand, the Middle Eastern lutes only have low frets and the term chapei derives from Sanskrit, which comes to thwart this track. Unless the chapei was born from the crossing of two musical instruments, that is to say the crossing of an old fretted zither of Indian origin but adopted in Cambodia during the Angkorian period and a Middle Eastern lute?

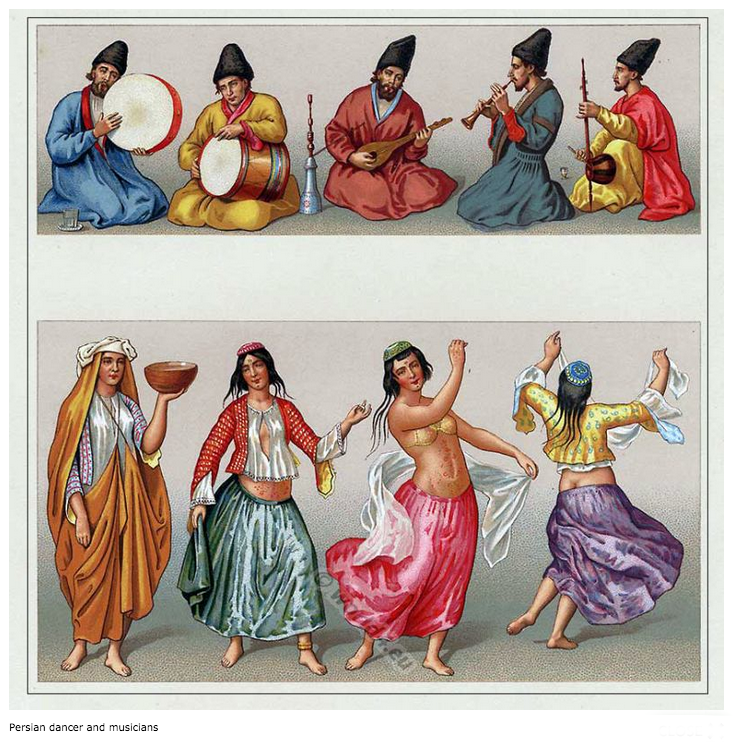

The miniatures below show some orchestras where long necked lutes, trichord fiddles, and various aerophones and membranophones play together.

The Indian track

As we have seen above, the term chapei derives from the Sanskrit kacchap(î) and is related to the turtle whose shell was used, and still serves, to manufacture the soundbox of some lutes. In addition, the high frets are a signature of Indian instruments. There is no formal proof that an ancient zither of Cambodia was equipped with such frets, but we can not exclude it either, as we have shown through the two representations of Ta Prohm Kel and Banteay Chhmar. It must be recognized that the high-frets and double-gourd resonators are fragile and difficult to transport. The lute partially alleviates this problem. One can then wonder why the ‘inventor’ of the chapei imposed itself the constraint of this long end (champu pien) so fragile?

Among the high-frets instruments of Cambodia are chapei and takhe. The latter could also derive from the aforementioned zither. Its origin is just as disturbing. Another instrument, called kropeu or krapeu - litt. crocodile -, was formerly shaped like a crocodile with high frets. These two instruments are not duplicative, they play in different music ensemble. Both instruments continue to be played in Myanmar.

The Chinese track

After considering the Middle Eastern and Indian tracks, it seems serious to consider the Chinese one. Certainly the terms chapei for Cambodia or kracchapi for Thailand are not of Chinese origin, but the instrument could have been named after the name of another lute he would have replaced. The Chinese track is serious competitor in several respects:

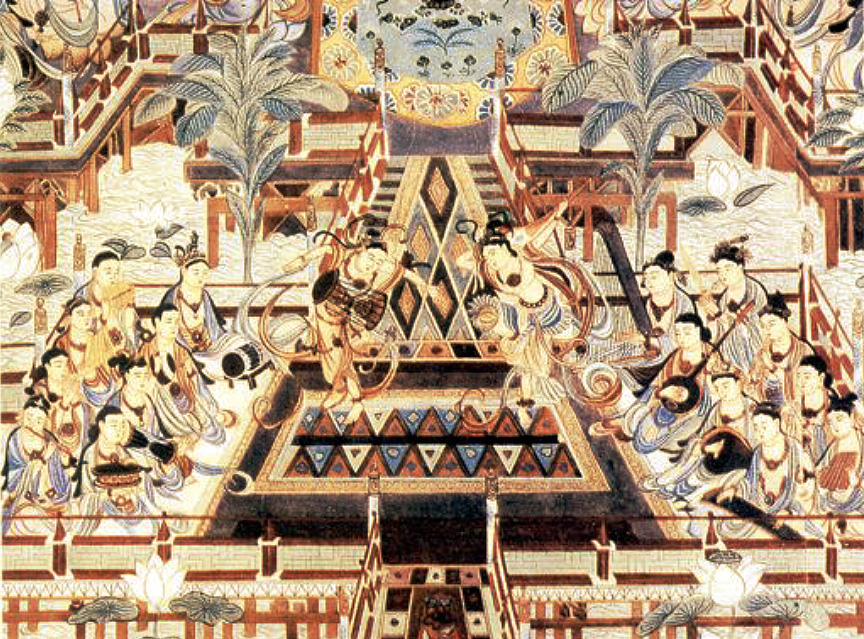

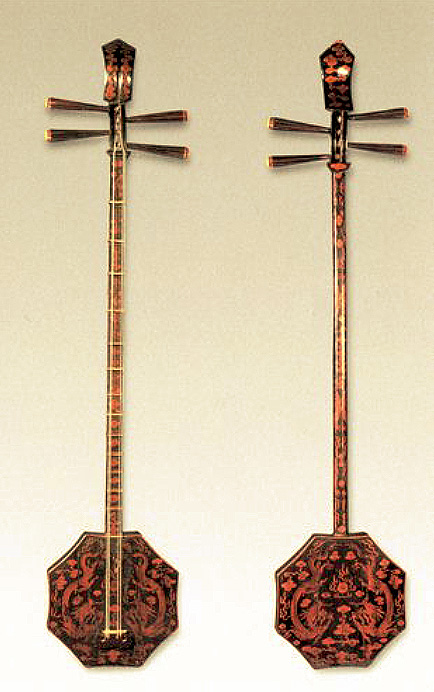

- Since the 4th-5th centuries, Chinese iconography shows lutes whose characteristics are close to those of the chapei (long neck, high frets, pegs, four strings).

- The tailpiece of the Chinese lutes is often similar to that of the chapei and kracchapi of the 18th and 19th centuries.

- The Chinese lutes also have frets at the junction of the neck and the soundbox as well as frets stuck on it.

- The head of a moon-shaped lute, ruan, from the Qing period (1644-1912), has a great similarity of form with that of the chapei, although less long.

Faced with this prospect, an ancestor of the chapei could have been introduced in Cambodia since many centuries, but no old iconographic trace, whether in Thailand or Cambodia, has reached us. The only ancient representations of lutes date, to our knowledge, from the second half of the 7th century in Thailand and the early 8th century in the Chams of Vietnam, and it is short-handled lutes with an oblong soundbox.

Below are the representations of Chinese lutes in ancient iconography as well as real instruments.

Provisional conclusion on provenance

In light of this brief comparative analysis, the Chinese track seems the most serious. Recall that Chinese trade with the Middle East has long been serviced through the Silk Road. Musical instruments have undoubtedly been at the heart of commercial and cultural transactions.

However, there are several gray areas:

- Why does the chapei have a name derived from Sanskrit?

- Why is the end part of the handle, non-functional, as long as it is binding to move the instrument?

- Why does the chapei play with the tro Khmer and the pei ar?

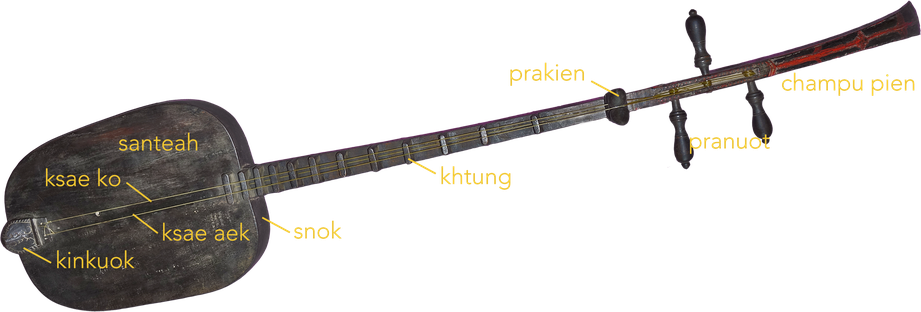

Organology and manufacturing

Traditionally, the soundbox (snok) of the chapei is made of beng wood on which is attached glued and screwed a table in roluoh wood. The case may also be made of jackfruit wood (khnor nang). The dimensions of the body are variable and can be either rectangular in form but with rounded corners - it is said to be in the form of a sima (monastery boundary) - or more trapezoidal in shape with rounded corners and it is then said to be in the form of muk neang (maiden face). Formerly it as also the shape of the leaf of the Bodhi tree. The soundboard (santeah) is almost always made of roluoh wood, more rarely of sâmraong. Formerly the soundboard was most often glued on the soundbox with fish glue, some screws sometimes consolidating the whole. A small resonance hole run is arranged in the center of the soundboard.

The handle is cut in a single block of khnor nang wood 105 cm long. But it is also often carved in wood of beng, kranhung, more rarely in krâsang or krâkâh .

To make the handle, the location of the nut (prakien) is first fixed, the distance of which to the resonance table is half the circumference of this sound box (the measurement is obtained by means of a string whose length is equal to the circumference of the sound box, the string then folded in two). It is then necessary to reserve a site for the pegs (pranuot) and then to carve the ornamental end of the handle which can measure from 10 to 70 cm.

From the nut there are 12 or 13 keys (khtung) made of bone, bamboo or beng wood (formerly ivory). The last two keys rest on the resonance table. They are kept with a little wax but not really glued, which allows at any time to move them to retune the instrument. The nut often has the name of the person or animal that it represents when it is sculpted: Neang Thorani, Têp Prânâm, Sva. It is made of trâyoeung wood.

In Cambodia, the size of traditional musical instruments is sometimes related to the size of the maker or the maker of the stallion; there is also a dimensional relationship between the various constituent parts. It is very likely that the so-called equiheptatonic range used by the Khmers was born from the manufacture of a flute with equidistant game holes. French ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet reports how a chapei maker met by him in the 1960s operated to determine the dimensions of the neck: “To manufacture the neck, we first fix the location of the prakian nut whose distance to the resonance table is equal to half of the circumference of this box (the measurement is obtained by means of a string whose length is equal to the circumference of the sound box, string which is then folded in two). All that remains is to reserve a place for the prânuot pegs and then carve the ornamental end of the handle which can be from 10 to 70 cm. From the nut, there are 12 or 13 khtung frets in ivory, bone, bamboo or beng wood. The last two frets stay on the soundboard. They are held with a little wax but not really glued, which allows at any time to move them and re-tune the instrument. The nut is often named after the character or animal he represents when carved: Neang Thorani, Têp Prânâm, Sva. It is made of trâyoeung wood.”

The frets

The frets of the chapei are high. They are different from those of the guitar and the Middle Eastern lutes, which, when they exist, measure only one to a few millimeters in height. In Cambodia, another instrument shares this characteristic: the takhê zither. More broadly, in Asia, there are high frets on most lutes. The list is too long to list.

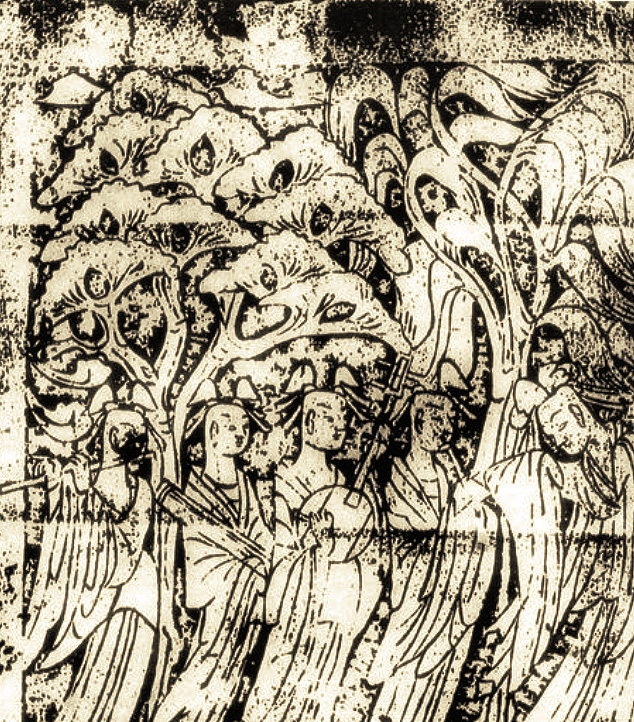

But a question arises: are the high frets originating in Cambodia or elsewhere? Very clever who could answer such a question. The iconography of the Khmer temples shows no instrument with such frets. However, we have already hypothesized, by observing the position of the hands of certain Bayon and Banteay Chhmar citharists, that their instrument was not directly related to the stick monochord zither, ancestor of the contemporary ksae diev. On the one hand, the position of the hands doesn't allow to play with the technique known as ‘partial’, on the other hand, the upper resonator is no longer placed on the chest but at the shoulder or above she. This would tend to prove that there was another type of zither that would have featured frets. It is known that such zithers have existed for a very long time in India. It is not unlikely that they would be played in Cambodia during the Angkorian era. That being said, there is no evidence that there is a link between the Angkorian zither, the takhe zither and the chapei lute as well. But it is a path of reflection and research. Let's continue our reasoning, even if we cannot prove anything yet. The fretted zither, which we have proposed a reconstruction, is fragile and not very sound. The creation of takhe as a substitute has the advantage of offering a more powerful sound. It remains heavy, however. The chapei is then an acceptable one between two sound power, acoustic interest and maneuverability. It is, moreover, both melodic and rhythmic. The technology of the high frets allows the musician to adjust the pitch of a note, to enrich the aesthetics of the musical playing by modulating the frequency at will, to create vibratos.

The strings

The strings are fixed to a tailpiece (kinkuok), glued and screwed on the table. The pegs are two, three or four according to the number of strings of the instrument. Formerly some instruments had four strings, notably those on the Royal Palace and on some instruments made in Battambang, wherever there was Siamese influence (indeed, in Thailand the chapei is played with two double-strings). However, the musicians have generally abandoned the two double strings since the silk threads were replaced by metal wires or Nylon threads (threads of fishing net). The most common formula is that of the chapei with two simple strings, formerly also from chapei to a lowest string and a sharp double strings, a solution that seems to have always prevailed in the countryside in almost all provinces.

In the case of chapei with two simple strings, the third peg serves to stretch a string which passes through a small hole made for this purpose through the frets and serves to not lost them during transportation.

The two strings of a chapei are tuned in fourth. The musician can change the pitch of the strings from one piece to another depending on the pitch of the root. But the fourth interval is generally maintained. The ksae ko string is used almost exclusively as a drone, rarely as a melodic string, except for the very great virtuosos. Most musicians play only on the sharp chord ksae aek. However, the fourth interval is not always accurate because it happens that the keys are not perfectly parallel, especially in the high notes. This does not bother the musician who almost always plays the low string empty.

In the 1960s, French ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet makes the following remarks about the chapei tuning: “The degrees are in line with those of the western scale. This is increasingly the case, not only in large cities but also in the countryside where transistor receivers also broadcast day-long music of Western variety. The evolution of the Khmer heptaphone is made unconsciously, by unreflective imitation of the standards heard constantly on the radio. At the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh and at the University of Fine Arts, agreement on the western scale was voluntarily established as a 'modernization' of Khmer music.”

The strings are now made of single-strand nylon. Traditionally, the two upper strings, accompanying, were larger than the lower strings, melodic. Sometimes The accompanying strings were made of metal. Some chapei have a single chord and two melodic strings. We don't know in what material they were before the invention of Nylon but we think they were twisted silk son as for most old string instruments.

The chapei can be played either with a plectrum or a tab attached to the index finger.

Playing chapei is said denh chapei.

If the playing on two strings is now widespread, we found on the Internet a Takhmao musician named Tet Thöne, who was 78 years old in 2010. He was himself a chapei maker and had been playing since 1947. Below are links to three videos about him.

Gender of chapei players

In the 20th century, chapei was played by men. Today this trend is confirmed but the growing number of women practicing. It must be recognized that the playing of complex

musical instruments by women is rare in traditional societies. In agrarian or agro-pastoral ones in which modern technology has not yet emerged, there is an obvious sexual disparity in

music practicing. In general, women sing and men play instruments. There are two major reasons for this. The first one is the absorption of women by household chores and food. In many

parts of the world where there is no running water, fossil fuel, or electricity, most of the time is spent on water drawing, collecting wood and preparing meals. Once all these tasks completed,

they still have to take care of children ans cleanliness. And as if that was not enough, the woman also takes care of crops and pets. Given such an observation, how could they find time for

studying a complex musical instrument?

The second reason is linked to taboos perpetrated by tradition. In West Africa, for example, drums remain the preserve of men. As to play a flute, a phallic symbol, it is better not to think

about it. Remains therefore to the women of the bush, the kitchen utensils they skillfully transform into percussion.

Émile Gsell's photo showing a woman playing chape in the

19th entury or the painting of the Silver Pagoda at the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh, both relate to palace musicians who have dedicated part of their lives to that. In this

particular case of royal or princely palaces, in Cambodia or elsewhere, there are many examples of professional female musicians relieved of daily tasks.

In the iconography of Buddhist pagodas, painters have placed musical instruments of all kinds in the hands of female musicians. We will now examine in what circumstances they play the Khmer

chapei or the Thai kracchapi.

Iconography of kracchapi in Thailand

One of the oldest representation of kracchapi in Thailand seems to date from the 18th century. The picture is a painting of the Ayutthaya School, owned by Jim Thompson's house in Bangkok. It is from the book about Jim Thompson's house.

Its represents Prince Siddhartha leaving at night the palace where he grew up.

In the current state of our research, this representation of kracchapi would be the oldest. We can already see the structure of Khmer orchestras phleng arak boran and phleng kar boran, that is to say by transposing the names of Khmer instruments: the chapei lute, the tro Khmer fiddle, the pei ar oboe with its large reed, the goblet drums skor arak or skor daey and a skor romonea frame drum seen from the front. While this last drum is not present in the phleng arak boran and phleng kar boran, the structure of the musical ensemble is similar. We know that traditional Cambodian orchestras were, and remain, geometrically variable according to the provinces, the formations themselves, the availability of musicians and instruments.

We have retained the French version (reworked) of the monk Dhamma Sāmi in his book “The life of Buddha and his main disciples” to describe the scene depicted here; it is recurrent in the pagodas of Theravada Buddhism.

“Returning to the palace, on this Monday of the full moon of July 97 according to the calendar of the Great Era, Prince Siddhartha headed straight for the main living room, without bothering to climb into the room where the princess was sitting and his baby. Once there, he lay down on his vast throne, sheltered by a large white parasol. All around him, young and beautiful women danced, others played musical instruments, others sang pleasant melodies, all richly dressed, carefully coiffed and pleasantly scented. Unlike the previous days, the prince no longer felt the slightest pleasure at these festivities. The kilesā (mental impurities) weighed on him now as long as he no longer accepted to undergo them, however tiny they may be. That evening, insensitive to the graceful spectacle of the dancers, to the delicate harmonies of the musicians and to the sweetness of the melody of the singers, he fell asleep.

Seeing the sleeping prince, the women of the palace, embarrassed, dared no movement, for fear of disturbing him in his sleep. They did not venture to leave, the order was not given to them. All remained on the spot. As the hour progressed, they fell asleep on the spot in a total disorder: the scattered bodies were directed in all directions, tongues hung, some snored, drooled, groaned, talked while sleeping, chewed, some had their mouths wide open, d others were half naked in the unconsciousness of sleep. After the middle of the night, the prince awoke. Contemplating the distressing spectacle that presented itself to him, he was finally satiated with kilesā. Disgusted, disgusted by this disgusting vision that made him think of a messy mass grave where corpses pile up pell-mell, he depressed. A thought crossed his mind: ‘And to say that I remained carefree, immersed in this world of sensory pleasures twenty-eight years!’

It is at this moment that the prince decides to put immediately at work his decision to leave the palace for the forest ...”

In almost all cases, the female musicians are represented asleep, as described in the original text. However, here, the princess and her baby are immersed in sleep while the musicians play for

awake spectators.

As is often the case for the illustration of mythological or historical texts, artists represent the musical instruments of their immediate environment, but not those of the time they illustrate.

So do not see there, or anywhere else, the musical instruments of the time of the Buddha.

The Buddhaisawan Chapel (Bangkok)

To understand the painting of Cambodia and Thailand of the late 19th and early 20th century, it is appropriate to plunge into the common history of these two countries and in particular the provinces that were sometimes Thai sometimes Cambodian. The curious Internet user can find some basic information here.

The Buddhaisavan Chapel in Bangkok was built in 1795 to house the statue of the Lion Buddha (Phra Puttha Sihing) of Sinhalese origin dating back to the 15th century. This chapel is now consecrated as a Buddhist temple and many worshipers frequent it daily, but no monk is attached to it. It contains the illustration of the 548th and last life of the Buddha in 28 murals made between 1795 and 1797.

The state of conservation of the panels is uneven and the paintings have been restored several times. The same panel can represent various events, sometimes anachronistic, separated by plant motifs (trees, bushes), minerals (rocks) or aquatic (ponds, rivers, seas). Important events are always painted on a red background and topped with zigzag decorations, typically Siamese.

The painting was made by the method called tempera, on walls washed and dried; the natural colors were applied on the dry walls, then stabilized with natural fixatives.

We present here the completeness of the panels of this chapel containing at least one kracchapi lute as they are beautiful and representative of the Buddhist culture of that time. The kracchapi are all played by women and, in a unique case, by a mythological being.

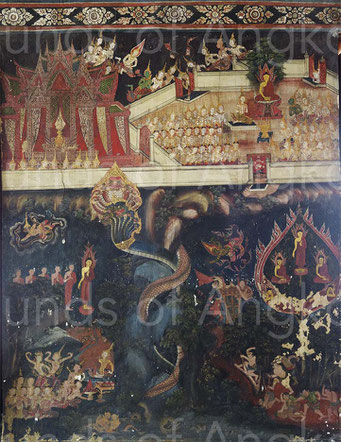

The visit to Tavatimsa heaven

“For three months during the rainy season, the Buddha preached to his mother and the gods, including ruler of Tavatimsa heaven, the god Indra. On his way to Tavatimsa heaven, the Buddha passes above the head of an evil serpent or Naga in human and princely form. Enraged, and assuming his serpent form, the evil Naga battles with another naga, Mogellana, who is a disciple of the Buddha, but to go/to avail, until Mogellana assumes the guise of a Garuda, the half bird half man enemy of the nagas the double miracle at Sravasti. To convince dissenters, the Buddha performs miracles in which a fully laden mango tree springs from a seed, and the Buddha himself appears in multiple forms simultaneously: as single walking figure, two seated figures and two reclining figures platforms erected by the dissenters on which to perform rival magic are destroyed by a storm caused by the green god Indra.”

The kracchapi shown here has an oval soundbox and three pegs. The frets are not visible.

The death and cremation of King Suddhodana

“The Buddha’s father, King Suddhodana, sends the ninth emissary to find the Buddha to return to Kapilavastu, to preach to his father and relatives."

Two orchestras are mirrored on both sides of the cremation tower. The kracchapi frets are not visible. The two resonance boxes have substantially different shapes; the one on the left is closer to the shape of the leaf of the Bodhi tree. The one on the right shows four tuning pegs.

The Buddha descends the triple staircase

“From Tavatimsa heaven down to the world of men, accompanied by the god Indra, the Brahma and celestial musicians, the Buddha descends the triple staircase of gold, silver and glittering jewels. At the time of the descent, a miracle enables the three worlds, of the heavens, earth and the hells, to be simultaneously visible to each other. After his descent to earth, the Buddha preaches to assembled followers.”

On this scene, two kracchapi are represented in two different contexts. In the upper left, Gandharva Pañcaśikha plays kracchapi. He holds in his other two hands two little hourglass-shaped drums that are one of the attributes of the god Shiva when he is represented as the God of Dance. Indra who holds the sword and the conch accompany him. The soundbox of his kracchapi is oval. The instrument has five tuning pegs but only three strings. Perhaps we should see there a symbolic representation: the five pegs could represent the five mountains of the Meru or remain the gods of Hinduism and the three strings, the three gods of Trimurti: Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva.

The second kracchapi is located under the stairway through which the Buddha descends into the world of humans. The instrument has four strings and the frets are visible. The musicians

have the same hairstyle as the chapei player of the Royal Palace of Phnom Penh photographed by Émile Gsell at the same time. It is clear from this detail that the Siam Court in Bangkok

and the Cambodia Court in Phnom Penh are close.

Death, cremation and entry into Nirvana of Princess Yasodhara

"Princess Yasodhara is the wife of the Buddha whom he abandoned at the same time as his son when he left the palace one night. Legend has it that King Udena had three spouses; two of them, Mâgandiyâ and Sâmâvatî, were fierce rivals: one was a disciple of the Buddha, the other was jealous and vindictive. While the Buddha was visiting the kingdom, each queen behaved accordingly: the first received him with food offerings, the second spread rumors and barked the dogs after him. "

It is also a lute in this story: "At that time, the king used to share his time equally between his three women, spending seven days in turn in the apartment of each of them. Magandyia, knowing that he would go the next day or two days later to Samavati's apartment, sent word to his uncle: ‘Send me a serpent, whose fangs you have soaked with it.’ This was done. The king had custom, wherever he went, to carry his magical lute, elephant charmer. In the soundboard of the instrument, there was a hole. Mâgandiyâ then introduced the snake and blocked the opening with a bouquet of flowers. For two or three days, the snake remained in the lute ...” Read more here.

The kracchapi depicted here has a soundbox whose shape is close to that of the leaf of the Bodhi tree. Twenty frets on the neck and six on the soundboard. Only two pegs are visible.

Engagement gift receiving, procession and celebration of royal wedding …

“This scene depicts the engagement, the procession and the celebration of the royal wedding of the Bodhisattva's parents, the Suddhodana King of the Sakya clan and Princess Maha Maya at the Kapilavastu Palace. The future couple, surrounded by members of the Court, face each other: between them is a bai sri (floral arrangement). On the left, Prince Suddhodana Gautama is flanked by Brahma with four faces and Indra with green. On the right are Princess Maha Maya and her suite.”

The orchestra is composed of six instruments. From left to right: small cymbals, fiddle, kracchapi lute, frame drum, goblet drum and a percussion instrument made of a bundle of hardwood and brass slats, tied together at one end called krap phuang (กรับพวง). The two drum players have their mouths ajar, which means they sing. This kracchapi has four coupled strings, seventeen frets on the neck and six on the soundboard. One of the characteristics of this orchestra is that both string players are represented as left-handed because the outfits are reversed.

Marriage of Prince Siddhartha with Princess Yasodhara

The hierarchy of the scene clearly appears from the bottom up: from the street to the Royal Palace. Seven musicians play in a dedicated space. The soundbox of the leaf-shaped kracchapi is of the Bodhi tree. There are thirteen frets on the neck and seven on the soundboard. The pegs are organized as a cross and the four strings are clearly visible. If the kracchapi player is right-handed, the fiddle player is represented as a left-handed player.

Prince Siddhartha leaves the palace where he grew up

This is the classic scene of the great renunciation, in which Prince Siddhartha leaves his wife and newborn son to seek to understand how to free humanity from suffering. Leaving the palace, he leaves the musicians and the dancers asleep. Then he meets four disguised divine messengers: an old man, a sick man, a dead man and a wandering ascetic, represented here as a monk.

The scene of sleeping musicians is, for painters, the opportunity to represent musical instruments that they themselves have seen in their socio-cultural environment. Depending on the cultural and intellectual level of the painter or his master, the choice of instruments and the quality of the details are variable. Here, one sees the neck of the kracchapi, that of the fiddle and three other instruments emerging from the abandoned bodies.

Organological and musicological teachings of the Buddhaisawan Chapel's frescoes

These paintings are rich in teaching about instruments and musical practices of the late 18th century. First of all, these orchestras must be considered as palatine and non-popular ensembles. Here, women play the instruments. The reality of popular music is quite different. The ensembles are constant from one painting to another, demonstrating that this orchestral model is adapted to events and enjoys great prestige since it is at the service of the Buddha, the court and the aristocracy. There is doubt, however, about the use of this type of orchestra for the funeral of Princess Yasodhara.

The number of frets represented is certainly not reliable. On the other hand, it can be concluded that all the kracchapi of the court, at that time, had four strings tuned in pairs to the fourth or the fifth according to tradition. This configuration provides the instrument with greater sound power and increased harmonic richness. Indeed, in music, 1 + 1 is not equal to 2. The slight phase shift that can result from a tuning difference between two adjacent strings creates harmonics that enrich the sound beyond the simple addition of the acoustic power of each of the strings.

The presence of female musicians at the court is in line with the court orchestras of King Jayavarman VII and probably other rulers, but we have no hard evidence about them.

The religious scenes depicted in this chapel also offer us a life touch at the court of Thailand in the 18th century through costumes, customs, dances and musical instruments, all of which are absent from the iconography from Cambodia.

The kracchapi through the iconography of a cabinet of the 18th century

An 18h-century cabinet of the Ayutthaya School, belonging to the National Museum of Bangkok, shows a musical ensemble similar to those of the Buddhaisawan Chapel, but with a gong chime. Thus, from left to right: an aerophone (oboe?), small cymbals, a gong chime, a barrel-shaped drum, a kracchapi lute , a fiddle, a second aerophone (oboe?).

On the left side of the cabinet, another kracchapi player seems to be the clown!

Iconography of the chapei in Cambodia

In Cambodia as in Thailand, the chapei is mainly represented in the paintings of pagodas and on old photographs, some published in postcards.

If you have photos of chapei yourself, you can send them to us using the CONTACT tab of this site. Thank you in advance.

Photograph of a female musician in the Royal Palace by Émile Gsell (1838-1879)

In the 19th century, the French photographer Émile Gsell created portraits of several female musicians of the Royal Palace, posing with their instrument. Thanks to him, we know one of the most beautiful chapei. It has four strings, tuned in pairs. We will notice the oval soundbox, fine pegs carved with a rare elegance and frets on the soundboard. This instrument has nine frets on the neck, one at the edge of the soundboard and five sticked on it. The pegs are either made of bone or ivory; they are comparable to the representations of the Buddhaisawan Chapel in Bangkok. Note the elegance of the fingers and nails of the musician and the characteristic hairstyle of that time.

Drawings of Louis Delaporte, late 19th and early 20th century

Louis Delaporte was a French explorer born in Loches on January 11, 1842 and died in Paris on May 3, 1925. Recruited because of his drawing skills, he left in 1866 in Cochinchina and was appointed with Ernest Doudart de Lagrée for the French Expedition of the Mekong, a mission of exploration and research to the sources of the river. He discovered on this occasion the site of Angkor. From these missions in Cambodia, he has left us wonderful drawings that still continue today to make us dream. Among them, some representations of musical instruments, including the chapei.

This drawing shows us one of the most aesthetic chapei that can be seen, with its soundbox shaped as a Bodhi tree's leaf. The tailpiece and the head are carved. It has two strings and three pegs: two are dedicated to the tuning of the strings and the third to secure the frets. We don't know if such a chapei existed in reality or if the artist embellished it?

The chapei through the Indochinese postcards

Postcards published during the French Protectorate are also a source of information on Cambodia's musical practices of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are not many of them representing a chapei but enlighten us on the formations and the instrumental mixes of this time.

This postcard dates from the early 20th century. The chapei is played by a woman. It has a pineapple-shaped soundbox, two strings, three pegs and twelve frets. The tailpiece is shaped like a lotus flower. Recall once again that the third pegs role is to avoid the loss of frets that are fixed with the wax in order to be moved at will to re-tune the instrument. But it seems that chapei with three strings (one for the accompaniment and two tuned in unison for the melody) also existed.

This engraving seems to date from the end of the 19th century. A note in pencil at the bottom of the image gives the date of 1874. There are, again, five female musicians playing a mixture of melodic drums and chordophones. Their hairstyle is similar to that of the musician of the Royal Palace photographed by Émile Gsell and the chapei, once again is similar, except the frets on the soundboard. Here they are only twelve frets.

This postcard, entitled "The Musician of Princess Kanakari", dates from the very beginning of the 20th century. It shows a mix of melodic percussion and stringed instruments. A total of ten musicians for eight instruments visible. It lacks drums and oboes. But it is likely that the oboes are replaced here by the chordophones. The chapei is very similar to that of Gsell's photo, especially from the point of view of the shape of the soundbox and the arrangement of the pegs.

This postcard of the early 20th century is marked “PHNOM PENH. Musicians playing for a public holiday.” The mix of melodic drums and chordophones is once again attested. We don't know, however, whether these eleven musicians were playing together at the same time. It's striking to imagine the low sound of the monochord zither fighting with the powerful gong chimes and drums.

Here, the chapei has a pineapple-shaped soundbox, twelve frets and three pegs. The number of strings is not discernible.

Organological and musicological teachings of postcards

These orchestral ensembles represented in Siamese painting from the 17th century to the postcards of Indochina at the beginning of the 20th century are, by their structure, the oldest evidence of acoustic coherence, and probably also symbolic, which prevailed until the Khmer Rouge revolution for wedding (phleng kar) and possession (phleng arak) orchestras. As early as the end of the 19th century, chordophones were substituted or reinforced for orchestras such as takhê zither, ksae diev monochord and / or melodic percussions such as roneat xylophones and kong vong and roneat daek metallophones. To the pair of thon and romanea drums, the skor arak or skor daey drums, numbering one to four, are substituted.

In the two images above, the musicians are not photographed in a playing situation but rather appear on the start, posing in front of the operator. Also, we have no real certainty about the functional mixture of stringed instruments with melodic percussion. However, the example of the cabinet of the school of Ayyuthaya of the 18th century described above, we are inclined to conclude that this type of instrument mix did exist.

The arak ensemble and the chapei of the Wat Reach Bo (Siem Reap)

We have devoted an entire chapter to the fresco of Wat Reach Bo. It is accessible here.

Wat Preah Keo Morokot (Silver Pagoda). 1898-1903

In this scene both colorful and strongly deteriorated by the onslaught of time, Isur proceeds to the marriage of Ream and Seda on Mount Kailash.

In this extraordinary wedding ceremony, there is both a phleng Siam orchestra (name used at the time for the pin peat) played by women and a phleng kar orchestra (now called phleng kar boran), also in the hands of women. The orchestra consists of a chapei dang veng whose form of the soundbox is not visible, a tro Khmer fiddle and two skor daey drums. If we compare this scene with the ensembles visible on the postcards presented above, we have noticed that here, the phleng Siam orchestra is physically separated from the phleng kar orchestra. We think that these two ensembles didn't play together but in time sharing.

National Museum of Cambodia

In 1914, Albert Sarraut, Governor General of Indochina, decided, with the agreement of the Cambodian ruler, to entrust George Groslier with the construction of a new archeology museum in Phnom Penh. The construction of the buildings, inspired by Khmer temples, lasted from 1917 to 1924. In 1918, part of the work was opened to the public and the museum was then called Museum of Cambodia. Finally, on April 13, 1920, on the occasion of the Khmer New Year, it is inaugurated by King Sisowath and takes the name of Albert Sarraut Museum.

The windows of the museum's entrance hall feature wooden shutters painted with scenes from the Reamker, including three musicians: a chapei player, a tro khmer player, and a ksae diev player. To realize these three paintings, we think that the artist had at disposal these three instruments as each detail is treated. There is nothing missing. It is an absolute perfection, a true testimony of the instrumental style of the early 20th century.

The chapei has four strings tuned two by two by four pegs. It has twelve frets, two on the soundboard. The artist created a trompe-l'œil by painting the veins of the wood on the sound box. No holes are visible in the center of the sound box. Curiously, the instrument is simply worn while the other two are played.

Wat Saravoan Techo, Phnom Penh. Late 1920s

The fresco we are going to study here is in the Wat Saravoan Techo in Phnom Penh, built apparently in the late 1920s. It is located above the East entrance, inside the building. This is the major scene of the pagoda: it illustrates the Descent of the Buddha from Heaven of the thirty-three gods down the triple staircase of gold, silver and precious stones. At the bottom of the stairs, an orchestra imbued with reality and mythology. From left to right, we can see: a first skor daey drum, a pei ar oboe, a tro khmer fiddle, a chapei dang veng lute, a pin harp, a ksae diev monochord zither and a second skor daey drum. Note also the presence of a singer (or narrator) who stands just below the Buddha. He holds in his hands a manuscript on oles. His straight right finger shows his function.

It is interesting to note that the chapei player is placed in the center of the orchestra and the gaze of all the characters under the Buddha converge on him.

Despite the historical quality of this fresco, let us mention some errors that crept into this orchestra:

- At the time when this fresco was painted, we are in the middle of the French Protectorate period. This is probably the reason why the artist painted landmarks between the frets, as they existed on the guitars introduced to Cambodia by the French.

- The tro Khmer was designed with a round soundbox in the manner of the fiddle tro sau of Chinese origin, instead of a triangular box. However, it has three pegs, signature of the tro Khmer.

- The shape of the harp and the arrangement of the strings are fanciful to say the least. It is clear that the artist never observed the Angkorian bas-reliefs that were, at that time, still buried in the jungle. However, it is interesting to note that there was, still in the 19th century, a memory of this instrument disappeared but become mythical. The neck ends with a bird's head, which tends to prove that the Angkorian harps maintained a strong relationship with this animal, outside even the heads of Garuda who adorned them in the 13th century. This would confirm the presence of the bird's head on “The Angkor Wat's harp”.

Wat Bakong. 1946

Wat Bakong, Bakong District, Siem Reap Province, is near the pre-Angkorian temple of the same name. It is decorated with beautiful paintings from 1946.

There are two scenes representing musical instruments. The scene here shows a restricted wedding orchestra phleng kar. There are four instruments and several observation errors:

- Chapei. It has four strings but the frets are equidistant and do not go to the sound box.

- Pei ar. The position of the hands is incoherent because the fingers of both hands close the same holes.

- Tro khmer-sau! This is a hybrid fiddle! Indeed, it has three pegs like the tro khmer but a soundbox of tro sau. Moreover, the bow is prisoner of the handle and not of the strings.

- Skor daey. We don't know what the artist intended, but the musician's face looks western and has a mustache. In addition, he seate differently from the other musician. It can however be justified by the playing of the drum that stays on the thigh.

Wat Bakong contains a second musical painting of a beautiful aesthetic. The artist clearly seems to have been inspired by the chapei. He borrowed the length of the neck, the four strings and the frets glued to the edge of the ‘rosette’ of the soundboard. The circular soundbox is either a pure creation of the spirit or a loan to the Chinese and Vietnamese lutes. As for the central opening, it reproduces that of the guitar, introduced in Cambodia by the French. The aesthetics of the head of the neck is inspired by the Angkorian floral decorations.

With his right hand, the Buddha asks the musician not to disturb him in his meditation. The choice of a female musician may have been dictated by the palatine practice underway at that time.

Wat Chedei, Siem Reap - 1940s

Wat Chedei is a Buddhist monastic complex built on the site of an Angkorian shrine surrounded by a moat. There is also a sanctuary painted in 1940s but destroyed in 2007. The walls are decorated but since the destruction of the roof, the paintings are delivered to bad weather. Among these, a chapei player. This musician is represented in a classic scene of popular Buddhism, that of the ‘Paroxysm of asceticism’ in which the future Buddha totally fasts and then changes his mind to eat only one grain of rice, a single pea or a single spoon of boiled beans.

Wat Kong Moch. Siem Reap. Early 1950s

Same scene as Wat Chedei, here at Wat Kong Moch in Siem Reap. The chapei is represented with three pegs and three strings.

The chapei and its cousins

The chapei dang veng has, or has had, several ‘cousins’ in Cambodia itself or more broadly in South-East Asia. All these lutes have in common a neck more or less long and high frets: chapei dang klei, chapei tung, kracchapi, đàn đáy ...

Chapei dang klei

In the past, some musicians played a chapei whose neck was shorter than that of chapei dang veng. This is the chapei dang klei. It remained popular in the countryside of Cambodia until the early 1960s. Its making is similar to that of chapei dang veng. However, its sound box was smaller and its neck only one meter long. Another difference was that the head was curved forward and not backward like the chapei dang veng and could be carved in various ways. This instrument was used in the wedding band just like its cousin. It was also commonly used in the Mahaori ensemble where its high pitch was appreciated.

Wat Kong Moch in Siem Reap offers us a representation of such an instrument in a 1951 (Buddhist Year of Rabbit, 2506) fresco depicting the Descent of the Buddha from the Sky of the Thirty-three Gods.

Vietnamese lute đàn đáy

In North of Vietnam, the trichord long-necked đàn đáy derives perhaps from the chapei but we can not bring any proof to this assertion. The only evidence he could derive from Khmer chapei is that he is the only Vietnamese heptatonic instrument; all other lutes are pentatonic.

The role of đàn đáy is limited to the accompaniment of professional singers of ca trù, a scholarly song born in the Lý period (11th-12th centuries). It is close by the length of its neck, the shape of its end but differs by its trapezoidal soundbox. The practice itself is distinguished by the fact that đàn đáy is always played by a non-singer musician accompanying a professional singer.

There are other lutes in Vietnam with high frets (đàn nguyệt, đàn sến, đàn tỳ bà, đàn tứ) but these lutes are pentatonic and derive from Chinese instruments.

Roles of chapei in Cambodian society

Chapei players perform at national festivals, village festivals and important events in Buddhist pagodas. They are also invited at official ceremonies or at the request of special interest groups. The radio and television of Cambodia devote it many hours of emission. For several decades, the most famous epic singers have toured abroad, performing in Khmer refugee communities in Australia, France, Canada and the United States. The most famous of them are Kong Nay and Prach Chhuon.

The chapei has long been an instrument of self-accompaniment of the singing of blind musicians, playing on the street for a living. One of them, Keo Samnang, was still playing in Phnom Penh streets in 2013.

Before the Khmer Rouge revolution, the chapei was part of the phleng arak ritual orchestra that accompanied the exorcist-mediums at their annual thanksgiving ceremony to spiritual entities, and the phleng kar wedding ensemble today called phleng kar boran (old wedding ensemble) as opposed to the contemporary orchestra.

How the chapei replaced the ksae diev at the Royal Palace of Phnom Penh in the 1960s

French ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet reports that in the 1960s, “The ksae diev of the Royal Palace of Phnom-Penh had no rope in 1962. The musician specialized in this instrument had not found it useful to replace it, this which was easy, and abandoned it in favor of the chapey. Since then, royal weddings have always been accompanied by an orchestra without ksae diev.”

The argument of sound power and musical interest is probably also to be taken into account. It must be recognized that the acoustic power of the monochord is so tenuous that the efforts made by the musician are annihilated by the other instruments. In the Angkorian era, when the monochord played alongside the harps, one can better understand the interest of this instrument. But since the instruments accompanying it become too powerful, only the nostalgic can deplore its absence.

Provisional conclusion

The history of the chapei is peppered with false beliefs and certainties. We don't know when and from where it arrived in Cambodia. Among the false beliefs, it is a stubborn one: it claims that the bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat show a chapei. The answer is clearly no. However, remember that the instruments presented in Angkorian iconography are those used in temples, at the royal court and on battlefields. Given the formerly high-fretted lutes in China and long-standing relations between the Middle Kingdom and Cambodia, it is not excluded that a lute belonging to the technological affiliation of the chapei existed in the popular classes or in the hands of street singers during the Angkorian times. We are not refractory to such a hypothesis, but it would be necessary to demonstrate it. To date, we have found no evidence.

So, researchers of all kinds, at work!

Videos of chapei

Keo Samnang is a blind traditional musician from Phnom Penh. He performed in the streets until 2013. Here he sings in embodying the character of a mother.

Kong Nay plays here with Amund Maarud. This video was shot on February 20, 2016 in Siem Reap during the 1st Friendship Festival.

Master Kong Nay plays chapei on February 15, 2016 in King's Road, Siem Reap, during the "1st Friendship Festival".

Kong Boran is the son of Kong Nay. He is young but talented. Succession is assured! This video was shot on February 15, 2016 at King's Road, Siem Reap, during the 1st Friendship Festival.