Bell tree

Angkorian sculpture proper (as opposed to pre-Angkorian) shows bell trees (or bell chimes) consisting of two to five elements. These sound tools are either hand-held or suspended. Numerous bells, both isolated and grouped, discovered during excavations, enhance our knowledge. This is one of the rare cases in Khmer archaeomusicology where we have both iconography and objects simultaneously. However, epigraphy does not inform us about the name of this object, unless we are unable to distinguish it. This is the only study in the world on this subject.

Updated: October 30, 2024.

Foreword

The present study is the result of a process of investigation spread over the period 2006-2023: iconographic research in Khmer temples, study of archaeological objects in museums and on the art market, recourse to intuitive archaeology. What's missing, however, is an analysis of materials, which we believe is possible since we have a few metal samples of broken bells.

We are publishing here all the iconography we have discovered (twelve scenes). If you would like to contribute further information, please use our CONTACT page.

Overview

Bell trees are not, strictly speaking, musical instruments, but sound tools used in ceremonies conducted by Hindu and perhaps Buddhist officiants during the reign of King Jayavarman VII. Not all of these contexts can be read in the iconography. However, they are present in the processional accompaniment of the sacred fire, alongside the half-vajra bells (Angkor Wat, third south gallery, west wing) and at funerals. At the Bayon, the bell tree is associated with conch playing and the recitation or chanting of sacred texts during religious ceremonies.

We are not certain of the specific name of this sonorous tool. The only known term for the bell in the Angkorian period is ghaṇṭā in Sanskrit, and katyāṅ in Old Khmer, provided by the inscription K. 669, 10th c. However, we have good reason to believe that this name was used to designate the bell tree, since the root of the Sanskrit term gave កណ្តឹង (kantung) in modern Khmer. We also have a few rare images of tree-bearers with bells.

We know nothing about how bell trees were played in the Angkorian period, but given what we know from ethnography, it probably consisted of the bells being struck up and down in a glissando motion; however, the separate striking of each element cannot be ruled out.

Archaeological artefacts

Many bells have been found in Cambodia, either in archaeological excavations or by chance. Some can be seen in the National Museum of Cambodia and in the archaeological collection of Wat Reach Bo in Siem Reap. From around 2009 to 2016, numerous examples were still on sale at the Russian market in Phnom Penh. We can attest to their authenticity. They came singly, in twos, threes and, in one instance... five, i.e. a complete tree. In the latter case, two bells were welded together by corrosion. The tree had been repaired because it contained two types of bells.

In archaeological finds and chance discoveries, bells have often been found nested inside each other, leaving traces of corrosion over time, like the one shown here. The bluish ellipse is the trace of oxide left by the smaller bell, which remained inside the bell for centuries.

Technical specifications

The sound elements of bell trees are immediately recognizable. They differ from simple bronze bowls. To the untrained eye, they may look the same, but bells have a circular hole in the center with several concentric lines on the outside. In addition, the inner rim is thick, generally triangular in cross-section. Around the base, on the outside, one to three equidistant lines encircle the bell. Some also feature shallow, concentric grooves on all or part of the outer surface, in the manner of a vinyl record (LP). After casting, some bells were machined on a lathe with a metal tool to reduce the thickness of the metal for tuning. In fact, given our experience of reconstructing these objects using the lost-wax casting technique, it appears that for the same object (same diameter, same height), the pitch of the note varies. Therefore, only by machining could the note be adjusted to harmonize the five bells.

We don't know what tonal scale the bells were tuned to, as to date we've been unable to find a single complete tree intact. Many of the bells found are cracked and therefore unusable. As mentioned above, the metal is very thin, just a few tenths of a millimeter. In the case of the most prestigious trees, users were probably looking for an overall resonance corresponding to a certain aesthetic that made for expert carillon making.

To date, no analysis of the metal composition of these objects has been carried out. We therefore do not know the percentage of copper and tin/lead, or whether any other metals were used. Perhaps the most prestigious trees possessed five or seven metals? What we can say, however, is that despite the fineness of the metal and its fragility, the centuries have not damaged the initial quality of most of the bells found in the excavations, provided they are not cracked.

Bells come in a variety of shapes, from skullcaps to domes to bowler hats. The photos below provide a global sampling of our knowledge on the subject.

Bell sampling

Profiles

Top views

Central grooves

Bottom views

Sound testing

In November 2010, we recorded elements of the Angkorian bell trees preserved at Wat Reach Bo in Siem Reap. We selected the best examples in terms of acoustics, although some were damaged. On November 23, 2010, we also reassembled a bell tree from disparate but sound-capable originals. This video is a sound summary of these experiments.

Below are three detail images of the first domed bell heard in the video.

Carried bell trees

In three instances at Angkor Wat, and only in this temple, brahmanas or rishis strike bell trees while carrying them.

Procession of the Sacred Fire. Angkor Wat, south gallery, west bay

In the Historical Parade scene at Angkor Wat (third gallery, south, west wing), two Brahmins each carry a five-bell tree in their left hands. They accompany the sacred fire. This is undoubtedly the most emblematic scene in Khmer sculpture featuring a pair (couple?) of bell trees. The bells are mounted on a flexible axis, a cord or chain. In his right hand, the officiant in the foreground is holding a striker with a handle that continues into a cylinder with latticework, perhaps a wickerwork or fabric.

Angkor Wat. Door pedestal. Tree with two bells

On the door jambs of Angkor Wat, there are thousands of medallions with individual or correlated meanings, sometimes veritable comic strips.

The scene presented below takes place in the forest, since the adjacent images depict wild animals and hunters. For this and subsequent examples, we will therefore refer to religious figures as "hermits" (ṛṣi (ऋषि) in Sanskrit and Old Khmer, sometimes translated as rishi) of the Hindu religion, numerous in Angkorian times and, even today, common in India and Nepal, where they are known as sādhu. In Hinduism, the rishi is considered either a patriarch, a saint, a priest, a preceptor, an author of Vedic hymns, a sage, an ascetic, a prophet, a hermit, or a combination of some of these different functions. In iconography, we recognize him by his high hair (ṛṣikeśa) tied in a bun since, according to tradition, most of them never cut their hair.

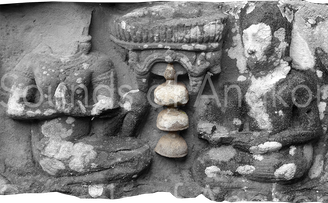

This appears to be a funeral ceremony. On the far left, a figure is shown with his feet up: the deceased. To our knowledge, there are only two instances of such a depiction of a deceased person at Angkor Wat, and only in the medallions of the jambs. The second image from the left shows a hermit reading a prayer book engraved on palm poles. In the center, a figure seated cross-legged. Then, in the fourth medallion, a tree player with two bells. The clapper is attached to the center of the lower bell by a tie. On the far right, a five-bell tree-bearer in front of the yoke and perhaps a bag containing bells in the back? We believe this last figure to be a bell-tree merchant, perhaps a hermit. Numerous occurrences at Angkor Wat, the Baphuon and the Bayon temples confirm this. (See "Bell tree bearers" below).

Angkor Wat. Door pedestal. Tree with four bells

Here, the scene is incomplete, having been destroyed by water infiltration to the right of the divinity. Again, this could be a funeral scene. There are several reasons for this:

- The presence of the bell tree.

- A hermit captures a cow whose calf, tamed by an acolyte, follows. The aim is to milk it to make the clarified butter needed to anoint the body of the deceased.

- Churning the milk in an earthen pot. This unique churning process is depicted as if it were a churning of the Ocean of Milk, with hermits on the left and figures lost to water erosion on the right. At the top of the scene, to the left of the crocodile, apsaras appear to be emerging.

- The presence of the crocodile, symbol of death, above Ganesha.

In the medallion line of the bell tree player, on the left, we see a hermit carrying offerings or ritual objects relating to funerals; his mouth is open, a sign that he is reciting or chanting a sacred text. In front of him, a fellow hermit carries and strikes a four-element bell tree. On the right, the deity Ganesha seated in lotus position with two attributes: the conch shell and the disk. In the churning of the Ocean of Milk, it is normally Vishnu who is featured. But here, in this singular scene, Ganesha replaces him. Here, he possesses both tusks, whereas he is normally represented with only one. His other two hands are in the anjali position.

Hanging bell trees

The Bayon features two occurrences of five-bell hanging trees, one in the south outer gallery, east bay, the other in the east outer gallery, south bay. There is also a three-bell tree in the north-west corner of the courtyard, among the unused blocks piled up by archaeologists when the temple was restored. We don't know whether the hanging trees had larger bells than the portable ones, but it's a possibility. Indeed, in the light of the image of the five-bell tree in the outer south gallery, east bay of the Bayon, it could be that the largest bell had a diameter of between 20 and 30 centimetres, given the proportions of the figures. Such undrilled bells existed in India until recently.

Trees hanging from five bells. Bayon, south outer gallery, east bay

This scene from the Bayon's outer south gallery, east bay, depicts a religious ceremony in the presence of a large, important figure whose sculpture is unfinished, perhaps King Jayavarman VII himself. The presence of pillars, curtains, parasols and trees suggests that the ceremony is taking place in an open building. On the far left, an officiant appears to be holding a booklet and a rosary. Behind him, a conch player, then the five-bell tree player. The size and nature of the clapper, connected to the center of the lower bell, is not explicit. We don't know whether the two scenes - that of the three religious officiants and that of the king's reception - form a coherent whole, as the figures turn their backs to each other.

Hanging five-bell tree. Bayon, east outer gallery, south bay

In this large offering scene (Bayon, third register of the south outer gallery, east bay), the bell tree is combined with the conch shell. The figure (Brahman) striking the bells appears younger than the one blowing the conch shell. His left hand is on the ground.

Three-bell hanging tree

The only representation of a tree with three bells comes from the Bayon, a high-relief piled among other blocks in the north-western part of the temple courtyard. The depressed line at the base of the real bronze bells is perfectly visible here. It appears to be complete with only its three bells. We don't know whether this block belongs to the temple's Buddhist period or to the later era of the Shivaite reaction. The lower element seems to oscillate under the action of the knocker.

Angkor Wat: pedestal with two bell trees

A pedestal in Angkor Wat's west gallery features two bell trees played by two different characters, with no causal link between the two scenes.

Angkor Wat. Door pedestal. Hanging tree with five bells

The scene in the upper register represents the only instance of a tree hanging from five bells in Angkor Wat. The clapper is integral with the tree to which it is attached by a flexible tie. The player, a man of undefined nature, faces what could be a hermit surrounded by two offerings. The circumstantial nature of the scene is not explicit.

Angkor Wat. Door pedestal. Hanging tree with four bells

In the scene in the lower register, the hanging tree has four bells and a clapper. The hermit faces a figure (congeneric?) flanked by an offering on his left.

Angkor Wat. Staircase pedestal. Hanging tree with four bells

In the second medallion of the central line, a hermit strikes a tree suspended from four bells in front of a meditating figure. In the adjacent medallions, there is no indication of a funeral. The other three medallions on the same line feature figures in positions of prayer and submission. This scene, devoid of any comprehensible context, remains obscure. However, the presence, in the lower register, of a tiger and fleeing figures, could be the source of a death and funeral ceremony. Such occurrences are present in all funeral scenes.

Angkor Wat. Door pedestal. Hanging tree with two bells

This set of five medallions features a tree player with two suspended bells (4th image from left), the clapper of which is integral. Unusually, the clapper protrudes outside the medallion. The figure in front of the bell tree appears to be a Brahmin or hermit. He is holding a prayer book. He turns his head to look at the figure behind him. Behind him, he appears to be carrying broken bells strung on an axle. At the front of the yoke, perhaps a bag containing new bells. The first image, on the far left, shows a kneeling figure. It's unclear what he's carrying, but it resembles the broken bells being carried by the carrier. The situation is justified by the presence of the tree with two bells; the other three are broken. In the second medallion from the left, a Brahmin or hermit prostrates himself before a deity (?) or ancestor (?) seated on a lotus flower and surrounded by two triangular offerings. Is this a ceremony to the ancestors?

Angkor Wat. Door pedestal. Funeral and hanging tree with three or four bells

This door pedestal is a real comic strip. The story seems to be about an accident and the funeral that follows. We see a wild elephant charging (?), a stumbling hermit, a character wrestling with a tiger (?), hermits praying, a character drawing milk from a cow's udder with his mouth, a churning scene, the anointing of the corpse with clarified butter* from the churning, and a four-bell tree player. The use of the bell tree at funerals is clearly confirmed here.

*In South Indian funeral rituals, clarified butter (ghi or neï) is used to anoint the body of the deceased, or only its nine orifices, so that the soul can escape more easily.

Bell tree carriers

A few rare occurrences of bell tree carriers have been found at Preah Khan d'Angkor and Angkor Wat. These are either two trees that naturally balance the load of the pallet, or a tree on one side and what we believe to be a bag on the other, containing individual bells of various sizes and pitches. Indeed, the elements of the bell trees are fragile, as the metal is very thin, on the order of a few tenths of a millimeter. We can therefore imagine that it was sometimes necessary to replace this or that cracked bell; archaeological examples of trees composed of at least two types of bells suggest this.

These figures could have been specialized traders belonging to the "circle" of ascetics. An image of a simple bell carrier found at the Baphuon and another in the south-western corner pavilion of Angkor Wat suggest this.

Carrier of two trees with five bells. Preah Khan of Angkor

On the right, hanging from either side of the palanquin, two trees with five bells. On the left, a Shivaite Brahmin with his trident. Although the Preah Khan temple was built during the reign of the Buddhist king Jayavarman VII, the Shivaite reaction to his death led to an iconographic shift towards Hindu imagery.

Carrier of a five-bell tree. Angkor Wat

Two elements of different natures hang from this ascetic's palanquin. At the front, a tree with five bells. At the back, what could be a bag carrying spare bells.

Carrier of broken bells. Angkor Wat

While the scene below appears similar to the previous one, there is some doubt as to the nature of the object on the back of the palanche. In the scene described above, this figure arrives at just the right moment in front of a hermit who is praying, but whose tree now contains only two bells, the others having perhaps been broken. The following hypothesis is put forward: this figure is carrying broken bells on the back of his pallet, which he has collected from other hermits to take back to the founder, who will recycle them to make new ones. In his bag are new bells of various sizes and pitches. It's worth noting that the bells on the same tree are gigognes, meaning that once the tree is folded up, they fit into each other, within the constraints of the link that unites them. Below is a photo of a batch of broken bells seized by the police from traffickers, and deposited at the Banteay Meanchey Provincial Museum.

Bell tree symbolism

The standard number of bells per tree is five. Although some representations, notably among the Angkor Wat medallions, sometimes show a lower number, we consider that this reflects the reality on the ground. Bells are fragile objects, and when one of them is broken or simply cracked, it becomes unusable, necessitating its dismantling. This situation argues in favor of glissando-based use rather than individual strikes.

The number five has a constant significance in the numerical framework of Hindu thought. It represents the number of mountains in Meru, the number of towers on the Bakan (Angkor Wat's central sanctuary), the number of superimposed corbelled stones forming the vaults and columns at certain windows in Angkor Wat, as well as the number of storeys in the towers of Angkorian brick temples, among others.

In the case of brick temple towers, the size of the storeys gradually decreases with elevation, while the bell shafts are arranged in the opposite direction, with the largest bell at the top. It's possible to imagine that, on a symbolic level, the logic should have followed that of the temple towers, but for practical reasons linked to the transport of the bells, it was necessary for them to fit into each other, like nesting dolls. We believe that funeral attendants moved from place to place with their bell trees. In this way, practicality took precedence over symbolism.

Bell trees outside Cambodia

Bell trees have existed and are probably still used in temples in China, Tibet and Japan. A few examples from the Net are compiled below.