Last update: December 5, 2023

Introduction

We will focus here on a type of ensemble of funerary music existing in Siem Reap and its surroundings: the kantoam ming. Although there are also funerary orchestras of similar structure in the country, Siem Reap has the peculiarity of having a carillon of gongs whose origins go back to at least the 16th century. This article amends, corrects and sometimes repeats certain elements of Trent Walker's article: ‘Funeral Music Along the Dangrek: The Buddhist Reinterpretation of Kantoam Ming’. In this article, the author is interested in how Buddhists give meaning to the sound and music of kantoam ming, and how they shape sound for Buddhist purposes.

Siem Reap and its surroundings counts three kantoam ming ensembles more or less active. Two of them owe their survival to the organization Cambodian Living Arts, which supported them from 2004 before they take off in 2009. The ensemble founded by Master Seng Norn is today the most active of both. That of the late Master Ling Srey is less so because its members have activities that do not allow them to free themselves to play during funerary rituals. As for the third, whose revelation dates from January 2018, he regularly plays at funerals.

But before going further, let's explore some fundamentals related to kantoam ming.

The various names of the kantoam ming ensemble

The kantoam ming ensemble of Siem Reap is referred to by various names, but we retain this terminology in order to homogenize the intention between researchers and facilitate indexed searches on the Internet.

One of the most common names is trai leak. Keo Narom in his book ‘Cambodian Music, p.10’ writes: “Trai derived from the Sanskrit word for three, while Leak or Lakana is a Pali word meaning a mark or trace. In Buddhism, all existence is marked by the three characteristics (lakshana) of suffering, impermanence, and lack of self.” She adds: "Ordinary villagers like to call this music according to its sounds such as kangroam ming, tatoam ming, toam ming. Others call the music toa ming as well, since it makes us think of moral actions and can cause us to become melancholy.”

Trent Walker also reports the term troem ming from a manuscript that once belonged to Master Ling Srey.

Name of the instruments of the orchestra

The orchestra consists of a small number of instruments whose names vary according to the ensembles.

- The kantoam ming ensembles in the Siem Reap area have one or two large gongs. These two gongs together are named kong dah pir thom. When the big gong is alone, it is called kong or kong thom. When there are two gongs, the biggest one is named kong chhmol or kong me (gong-mother). The smallest one is called kong nhi or kong koun (gong-child). But it was probably not always so. Indeed, the ethnic minorities living on the borders of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam name the two largest gongs of their sets, gong-mother for the first in size and gong-father the second. The children are the ones who come after both of them. Some authors and musicians consider that the big gong is male and the small, female. In our opinion, this is a cultural nonsense, even if this belief is respectable. In traditional Khmer society, the feminine is dominant. In the proto-Khmer, all that is great is feminine, starting with the largest gong. We do not know how to explain this ‘deviance’ except the Buddhization of concepts throughout history. Buddha is a man and his representatives, the monks, are also men. In addition, modern Khmer society is dominated by men. So it's not surprising that the gong, which opens and closes cycles, becomes male!

- Drum: skor thom, skor yeam thom

- Gong chime: kong peat, kong peat vung touch

- Oboe: pei, sralai, sralai troem ming.

Geographical distribution

Keo Narom mentions (p.11): “In the beginning of the 1990s, we only found one Trai Leak ensemble practicing in Siem Reap Province ; we also heard the sound of this type of music played by cassette in Siem Reap, Oddar Meanchey, and Banteay Meanchey Provinces and in some areas of Battambang Province.”

Trent Walker mentions: Kantoam Ming is “known through a variety of onomatopoeic names in Khmer communities along the Dangrek Mountains that divide the Cambodian provinces of Banteay Mean Chey, Odd Mean Chey, Siem Reap and Preah Vihear, and the Thai provinces of Buriram, Surin and Sisaket. Kantoam Ming is now practiced in only a handful of villages throughout this region.”

Ancientness of the instruments of kantoam ming

Hanging gongs, gong chimes and oboe appear for the first time in the iconography, on the bas-reliefs of the north gallery and on two frescoes of the central sanctuary of the temple of Angkor Wat (Bakan). According to an inscription, the bas-reliefs date from the 16th century. As for the frescoes, we can just say that they date from the same period.

The barrel drum appears for the first time in the iconography of the Baphuon in the 11th century.

The instruments of the north gallery of Angkor Wat

Part of the bas-reliefs of the northern gallery of Angkor dates from the 16th century except The Battle of Asuras and Devas, in the west wing whose style and instruments are typically of the original style of Angkor. This large bas-relief depicts the classical martial-arts instruments found in Bayon and Banteay Chhmar. Despite its antiquity, its making is not as neat as the rest of the bas-reliefs of the temple.

As for the Krishna Victory over Asura Bāna, east wing (16th century), it presents new instruments and technical innovations compared to what existed in the 12th century; on the other hand, its making is mediocre. On certain scenes, instruments of any kind, without apparent coherence of association, are spread before our eyes.

What are the new instruments and innovations compared to the existing?

- New instruments: gong chime, oboe, block flute, bossed gong, C-shaped trumpet. Note that the end-mouth flute probably already existed but its representation is a first.

- Innovations on the existing: addition of supports to portable barrel drums and to those on bearing.

Most of these instrumental archetypes have survived in contemporary Cambodia. The only ones that have disappeared are the trumpets, with the exception of the horns made of buffalo horn.

Instruments from R. to L.: hourglass drum, pair of horns, barrel drum with integrated support, conch, gongs chime, pair of oboes, pair of bossed gong, large drum with support, cymbals, monochord zither with single resonator, three block flutes. Angkor Wat, north gallery, Krishna's victory over the Asura Bāna.

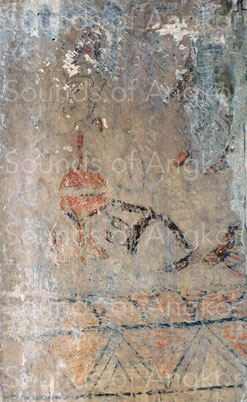

The frescoes of the central sanctuary of Angkor Wat

Two frescoes representing two orchestral ensembles have recently been spotted in the central sanctuary of Angkor Wat (bakan), one situated to the south and the other to the east. The first one is complete but the second one only partial because of the degradation of the wall.

The first fresco was mentioned in an article published in 2014 by Noel Hidalgo Tan: "The hidden paintings of Angkor Wat". The second stems from Patrick Kersalé research.

These two discoveries are important in more ways than one:

- They highlight the antiquity of the pin peat musical ensemble of Cambodia and its Thai and Laotian cousins.

- If most of the instruments, in their definitive or archaic form, were known to us by the bas-reliefs of the north gallery of Angkor Wat, their reunification into a coherent whole was hitherto unknown.

- The xylophones composing the contemporary pin peat appear here for the first time in the history of Cambodia.

The southern orchestra

The fresco must be read from left to right, like Khmer writing. The very attenuated original colours (photo 1) were enhanced thanks to a chromatic manipulation technique developed by ourself (2).

This fresco shows us eight instrumental elements. From left to right: two gongs, two drums, a gong chime, a xylophone, an oboe, a trumpet.

- Gongs: On the extreme left, a musician holds a mallet in his right hand. In front of him, two bossed gongs of different sizes are suspended inside a frame; its upper left part seems decorated.

- Drums: To the right of these two gongs, two drums in the barrel shape are placed horizontally, one behind the other. To the right of the drums stands the drum player. A vertical strip between his sarong and his conical headgear represents the playing stick(s).

- Gong chime: In the middle of the fresco, a gong chime with of eight gongs and two decorative elements in triangle at the ends. At the centre of the instrument stands the musician with two mallets.

- Xylophone: The cradle-shaped instrument located to the right of the gong chime is obviously a xylophone. The probability of a metallophone with bronze or iron blades still present in contemporary pin peat orchestras must be excluded because of the cradle shape. Indeed, the heavy metal blades are always laid flat while those of xylophones, wood or bamboo, follow the curved line of the soundbox. The ends seem to curl like scrolls. Above, we can distinguish the musician with two mallets. This is the first xylophone representation in Cambodia.

- Oboe: On the right and partly above the xylophone, an oboe without bell has an oblong pirouette similar to that of contemporary Khmer instruments, cut in a coconut.

- Trumpet: At the extreme right, a trumpet player. The instrument, long and fine, ends in a conical bell. There is little doubt that this instrument must be metallic.

The eastern orchestra

The east painting is very degraded. Unlike the south one, it spreads out at the same time on a large section of wall facing east and on a narrow return of angle oriented to the north. The left part of the large panel is illegible.

On this very degraded fresco, six instruments remain. From left to right: a trumpet, a gong chime, a xylophone, a cylindrical drum, a barrel-shaped drum, an oboe.

- Trumpet: On the extreme left, the trumpet is similar to that of the south panel, forming an angle of 45 ° with the axes of the ground and the wall. The pavilion is directed northward while the east panel turns to the west.

- Erased instrument(s): On the left of the gong chime, one sees the back of a musician's clothes represented in profile. One or two instruments seem to have disappeared.

- Gong chime: It seems to have nine gongs. If we compare it graphically to the south one, the artist represented the gongs by a single round of color without distinction of the nipple. By comparing the representation of these two chimes with those of the north bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat, the counting of eight and nine gongs is corroborated.

- Xylophone: Its representation is in all respects similar to that of the south.

- Barrel drum: To the right of the xylophone, we find the outline of a barrel-shaped drum similar to the Khmer skor sampho. The support, if it existed, is not visible.

- ‘Long’ drum: To the right of the barrel drum, a ‘long’ drum. This type of instrument is also depicted in the pin peat orchestra of the Phnom Penh silver pagoda in the wedding scene between Ream and Seda (photo 6). Its use persists but has become scarce in Cambodia. We call this drum simply a "long drum" because it could be cylindrical, slightly conical or like an elongated barrel-shaped. Typologies still vary.

- Oboe: Its representation is in all respects similar to that of the south.

Comparison of South and East instruments

One question arises: are they two orchestras or one? I have already mentioned that on the Southern fresco, there are no cymbals, yet indispensable in the orchestras if one refers to the first iconography of the seventh century until the present time. However, the small cymbals are painted on the return of North angle, as a link between the two frescoes. The presence of two gong chimes, two xylophones and a samphor drum is consistent with what we know today in the pin peat ensemble.

We know that the pin peat consists of female and male instruments of different heights. In playing configuration, they are generally arranged in pairs, one next to the other, but for graphic necessities, they have been dissociated in two sections with as a structural link the cymbals that emphasize the pulsation.

6. Pin peat orchestra belonging to the Reamker fresco of the Silver Pagoda (Royal Palace, Phnom Penh, 1903-1904). It contains most of the instruments of the Angkor Wat frescos. From L. to R.: roneat aek xylophone, skor sang na drum, kong vong gong chime, skor daey drum, skor thom drum, chhing small cymbals, skor sampho drum, sralay oboe, roneat tong xylophone.

Arrangement of the instruments

The arrangement of the instruments is not the result of chance. From left to right, they structure the musical cycle, from the lowest to the highest, from the slowest to the fastest. The more acute the instrument, the more it generates notes. Given what is still known today with the pin peat ensemble, the xylophone plays the same time division as the gong chime, but allows a greater velocity and consequently cuts the time more deeply.

Decorative band under the orchestra

The decorative band under the south orchestra (2) is also no coincidence. Seven symbolic flowers are visible but they were probably eight at the origin. Each consists of four large petals and four small ones located respectively at the four cardinal points and the four intermediate directions. Each flower is framed with a black line. They probably represent a kind of symbolic score of musical temporality. The large petals represent the main sequence of the cycle underlined by the gongs and small ones, the temporal mark of the drums. If there really are eight flowers, it could indicate that the music was structured over eight cycles or a combination of eight ones.

The painter and dating

There is no doubt that the author of these two frescoes is the same person. This artist is probably at the origin of numerous paintings spread over the whole temple of Angkor Wat if one judges some details.

These paintings could be dated according to the nature of a sailboat present in the collection of the frescoes of Angkor Wat. It could be a Dutch ship of the 16th century.

In addition, the chimes of eight and nine gongs are attested in the 16th century on the bas-reliefs of the north gallery of Angkor Vat. In the 17th century, an inscription of donation to Angkor Vat (IMA 36)* mentions a chime of sixteen gongs. It could therefore be later. These paintings could then be located between the 16th and 17th centuries.

*Pou-Lewitz I Inscriptions modernes d'Angkor 35, 36, 37 et 39 I In: Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. Tome 61, 1974. pp. 303-308.

False beliefs

It is appropriate here to take stock of the false beliefs conveyed by the oral tradition and enhanced by an excessive attachment to the past. Even if certain technological, ritual and intellectual reminiscences existed in the time of the Buddha or more recently in the Angkorian period, we cannot blindly confuse music and the orchestras that serve it with those of the past. The various personality interviews, whether venerable Buddhists or masters of music, broadcast by all kinds of media, contribute to endorse false truths. Nor does the scientist hold any historical truth, but tries to demonstrate, with proofs, that reason can substitute for the perpetuation of pseudo-beliefs. Here are a few :

- “The musical instruments of the kantoam ming are Angkorian.” If we refer to iconographic and epigraphic sources, the only existing instruments for ritual music are chordophones and percussion, which does not exclude that there are other instruments whose nature is unknown to us or for which we do not know how to make the historical link. The first appearance of the gong chime and oboe in iconography, dates from the 16th century, in Angkor Wat. The confusion is maintained by the fact that this temple dates from the beginning of the 12th century. Some authors have mentioned, perhaps rightly, that the bas-reliefs completed in the 16th century had been previously drawn on the walls of the northern gallery of Angkor Wat, but in my opinion, modifications have been made, particularly concerning the musical instruments. The harps already seem not to exist at this time. Only the monochord zither has survived and is represented in these bas-reliefs.

- “The kantoam ming orchestra dates back to the time of the Buddha.” How can one imagine that an orchestra can cross time and space over such a so long period. While it is clear that music and songs have accompanied funerals for a very long time, the kantoam ming only dates from the so-called post-Angkorian period, with the development of Theravada Buddhism.

- “Cambodian Living Arts (CLA) has reinvented the 9-gong chime”. The kantoam ming set and its nine gong chime have not been reinvented by CLA. The best proof lies in the fact that the third set that had escaped the vigilance of CLA and therefore not supported by them, use this type of chime. Better proof still, the Surin orchestras, the Khmerophone province of Thailand, play these same instruments.

Ancient filiation of kantoam ming

There is the question of an older origin of kantoam ming. Laurent de Lavoisier (1743-1794) said: “Nothing is lost, nothing is created: everything is transformed.” Thus, the kantoam ming is not a revealed or a fallen from the sky concept. It finds its roots somewhere.

We have no scientific knowledge of Angkorian instruments other than the iconography of temples, mostly of Indian origin. It is remembered, musical instruments palatine, religious (Hindu and Buddhist under the reign of Jayavarman VII). But in parallel with these practices, there were popular music to accompany the events of daily life: birth, marriage, funerals, calendar celebrations, house inauguration, deflowering feast of young girls (mentioned in the text of Tcheou Ta- Kouan), etc. But where to find any instrumental anteriority?

The chimes of gongs have been blooming throughout the continental and island Southeast Asia for centuries (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, Java, Bali ...). What characterizes most of these societies are the sets of gongs where each is played by a single musician. These sets are usually accompanied by one or more drums, sometimes with one or more melodic instruments (flute, fiddle, oboe ...). In Cambodia, there still exist minority peoples, Ranatakiri and Mundolkiri (Jarai, Tampuon, Kreung, Bunong…), playing such sets, especially for their funerals. These same populations, and others, in Laos (Lawae…) and in Vietnam in particular, play the sets including gongs and a drum. Given the vastness of the geographical area in which these instruments are played, it can be hypothesised that such ensembles already existed in the Angkorian period. It is also known from legends and concrete facts dating back to the first half of the twentieth century that such ensembles were played for martial purposes. The bas-reliefs of the north gallery of Angkor Wat corroborate the use of the big drum, the pair of great gongs and the chime of gongs for such purposes.

But how and why do we go from a set of collective gongs to an individual gong chime? We will consider two hypotheses starting from the strict reality of considering each set of gongs as one and the same instrument, each element of which is struck by individuals evolving through a collective thought system.

- There is a propensity of human nature to individualize, even in societies whose way of thinking and living is truly collective, which is the case of the traditional Khmer society where survival depended on the group, especially through rice.

- The economic dimension exists, even in the world of music. So how is it possible to play the same music with three musicians instead of ten to reduce the costs: about the gongs, by grouping them to a individual gong chime.

We think that the transition from the collective gong sets into a single instrument could be an initiative of the court for military purposes and then drift into religious uses at the service of the people. It should be noted, however, that the Khmer did not seek to replace the two great gongs which represent the couple, a fundamental social entity. It should also be noted that funeral ensembles with gong(s) and drum exist elsewhere than in Siem Reap but don't include gong chimes. We don't know if it existed in the past. However, these chimes exist precisely where the radiant power of the Khmer Empire was exercised until the mid-15th century, and where the kingship relocated provisionally in the 16th century.

The musical structure of kantoam ming, with these short melodic cycles repeated to infinity, is similar to the repertoire of gongs of contemporary ethnic minorities of Ratanakiri and Mondulkiri, with however an additional spatial dimension related to the fundamentals of Buddhism. See chapters below. When we speak of a cycle, we also speak of a circle. Kantoam ming instruments are circular (vertically suspended gongs, drum, chime gongs). Hanging bossed gongs have the acoustic ability to resonate. They are in the image of power: the central nipple represents the temple of state and the depression that adjoins it, the moat. If the gong gradually infiltrated the village social fabric, it was probably not so initially. In South-East Asia there is a material duality: the bronze at the court or in the centers of power, the bamboo in the village. For these reasons, it is likely that the music of kantoam ming was once the prerogative of the court.

Instruments and sounds of kantoam ming

Trent Walker describes the different interpretations of the sounds produced by kantoam ming instruments and their interpretation through Buddhist thought. We invite you to discover them in his article: “Funeral Music Along the Dangrek: The Buddhist Reinterpretation of Kantoam Ming.”

We give here a lightened version.

- The kong peat vung touch has nine gongs. When it is played the sound ting tang tik tak is heard, like the sound of gentle rain falling from the sky and striking wistfully against the leaves or various other natural objects below, reminding us of this fragile life, which comes into existence only to be struck by painful or pleasurable sensations, birth, old age, sickness, and death, the state of impermanence from which there is no escape.

- 2. The kong dah pir thom, consists of the kong chhmol and the kong nhi or the kong me and kong koun. The kong chhmol is 60 centimeters in diameter while the kong nhi is 50 centimeters. When they are played, one hears the sound ming mung ming mung, a sound like rumbling thunder in the sky, or like the sound of someone gravely ill, a loud sound that tightens the chest to the point of cracking open, and leads to be being stirred by the Dharma, filled with horrific grief, for this life of ours contains not a shred of immortality. All of these songs are to guide us to the emotional experience of bliss and peace, joined together with a mental experience endowed with insight.

- 3. The sralai troem ming is similar in shape to the pei pok. Its body is made of hardwood, and has seven holes just like the sralai pin peat. When it is played, one hears the sound of a cicada wailing loudly, a sound so piercing and melancholy, so vastly distant, that it reminds us regretfully of this body and our external possessions that are the origin of lust and desire, the basis of the cankers and defilements.

- 4. The skor yeam thom is 60 or 70 centimeters wide and 90 or 100 centimeters long. When it is played, one hears the loud sound kdung kroam kdung kroam, like the sound of thunder and lightning breaking apart the clouds and pouring forth their rain all at once, or like the sound of Lord Death himself, commanding his henchmen to cut short the lives of men and beasts, without the slightest regard for their welfare, depending on karma and its results to decide.

But kantoam ming is not the only one to imitate the sounds of nature. The instruments of the phleng Khmer ensemble, also imitate the sounds of nature. Jacques Brunet reports a Khmer legend collected from the musician In-Kompha, from the village of Kompong-Luong (Kandal Province) in the 1960s*.

Here is this legend: “While he was only a farmer, King Trâsâk Phaem used to listen to the sounds of the forest and the cry of animals: frogs, cicadas, buffalo toads, crickets and all the animals that can be heard around you. He also liked the whistling of the wind and the roar of thunder. When he came to the throne he soon became very sad, alone in his palace; he greatly regretted his old profession, and dreamed only of the song of birds, the cry of monkeys, and all the animals of the forest. He decided one day to gather the scholars of his palace to ask them to create instruments capable of imitating the cries of the animals he heard in nature. The scholars, in order to please him, began to invent various instruments to meet the wishes of the King. Thus they made the pey to imitate the cry of crickets, the flute khloy for the song of birds, while the tro Khmer imitated the sound of the wind and the drums skor the sound of thunder. At that time, music was played to imitate the sounds of nature, and it was only later that other scholars perfected and diversified the instruments to become what they are today.”

*(In : L'orchestre de mariage cambodgien et ses instruments. Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. Tome 66, 1979. pp. 207-208).

Spatial displaying of musicians and instruments

The position of the musicians during the game is singular; everyone looks in a cardinal direction. This fact is mentioned for the first time by Keo Narom in his book “Cambodian music”. “The three musicians of the Trai Leak Ensemble sit with their backs facing each other, thus signifying old age, fire, the spirit, and death in which we are separated from others.”

Even today, the musicians of the new generation are perfectly familiar with this traditional position, but sometimes they take a certain liberty with this concept, even in funerary context, tending to look in the same direction.

The arrangement of the chime of gongs and oboe naturally follows the position of the musicians. The gongs and the drum have a position to respect: the smallest gong is positioned near the drum while the largest is opposite.

Temporal structure of music

Notwithstanding the belief that the position of the musicians reflects the dislocation, we think that this position is structural and could go back to the Angkorian era. Khmer temples like Bayon and Phnom Bakheng, for example, had the ambition of structuring both space and time. It seems that kantoam ming is based on this same concept. The musicians gaze in three of the four main cardinal directions while the drum and gongs structure a division of cyclical Khmer time inherited from India. This observation leaves me to think, without any other proof however, that this orchestral structure and this music could have existed since the Angkorian period, but with other instruments, in particular sets of gongs. Let's examine percussion and their playing.

Musical scale of kantoam ming

The first sensation that emerges for an ear musically exercised to listen to the music of the Royal Palace of Cambodia is that of a strange falseness. The gong chime one doesn't always respond to the scalar canon of Khmer music. Why? We think there are many reasons for this and it has not always been so.

- At the moment of the creation of a kantoam ming ensemble, the gong chime and the gongs are tuned according to the oboe. But over time, the material that allows the tuning of the kettle gongs of the kong peat (wax and melted lead) disintegrates and falls to dust under the action of repeated strikes and aging of materials. The ear of the musicians is accustomed then to imperceptible changes of height without they pay attention to it over the years.

- One can also imagine that musicians operating in other types of orchestras, such as pin peat, or from outside, might find that the kong peat is badly tuned; but they could not afford to go and find the master to tell him, this would be unseemly in Khmer culture. Everyone obeys and respects the teachings of the master.

- On the kantoam ming ensemble, we have already mentioned, the three musicians look in three different directions. According to the belief, this represents the dislocation of the body and the nineteen souls or vital principles, according to the interpretation of each one. This funeral music is perceived by the Khmers as emotionally intense. It is generally inconceivable to play it outside funerals, which poses a problem for musicians who have to find a place of rehearsal outside any inhabited area. If the two ensembles supported by Cambodian Living Arts agree to play outside the funeral ceremonies to testify to the existence of kantoam ming, the orchestra of Wat Trach only plays in the context of funerals. Music related to dislocation may be more intense in Khmer perception if the sounds themselves are dislocated.

- In general, the notion of tuning as it is conceived in the West for example, is not of capital importance for the Khmers.

Playing opportunities

The kantoam ming ensemble is exclusively dedicated to funerals. In the 1990s, Keo Narom mentions: “Trai Leak is played when the deceased lies in the home prior to cremation. When the corpse leaves the house, followed by a procession, the Trai Leak music is no longer played.”

Today this ensemble is performed in front of amateurs of ancient culture of Cambodia because the setting of privileged moments specially organized by Cambodian Living Arts. The music and the orchestra are then presented by playing and talking by the musicians themselves.

During our study, we followed Master Seng Norn's ensemble, now led by Pong Pon. The ensemble was invited for various occasions. It seems interesting to mention here, as part of the musical history of Cambodia, the few events we have attended.

- Funeral of the great architect Vann Molyvann. The ensemble played at the home of the deceased where the body was exposed for four days and finally on the funerary field.

- Funeral of Venerable Wat Preah Prom Rath's mother in Siem Reap. Duration: five days.

- Collective funeral in the Banteay Srei area, near Phnom Dak. Duration: two days.

Articulation of the kantoam ming with other stakeholders

On the ceremonial field, the music of kantoam ming is part of a vast organizational process. It is regulated by tradition and varies according to the region, the organizers or the ease of the family. The sound space is shared between the prayers and songs of the monks, the processional music of the traditional ensemble klong thank or klong chhneah, possibly the military music, the speeches of the family and officials. The kantoam ming music, like that of the pin peat in the context of Buddhist ceremonies, fills the temporal spaces not used by these various actors. This music doesn't have, strictly speaking, a semantic message to deliver. It's not a priority but contributes to creating a funeral atmosphere to which Khmer people are particularly sensitive. It often happens that kantoam ming and pin peat share these vacant temporal spaces.

The life of the troupe during the funeral

We will describe and analyze here the material organization of Vat Svay Thom's troupe during a funeral process that lasted six days, from December 6 to 10, 2017 at Wat Preah Prom Rath in Siem Reap. It was a funeral in great pomp of the mother of the venerable of this pagoda.

The kantoam ming's troupe of Vat Svay Thom was present throughout this period from 4 / 5:00 pm to 11:00 am and from 1:00 pm to 9:00 pm. Each day, however, was punctuated by numerous breaks during which other priority speakers officiated. This requires a particular organization. The musicians are semi-professionals, in the sense that they share this musical practice with other activities. If there are only three to play, they are actually a team of five people who take turns:

- Pong Pon: direction, oboe, gong chimes, drum-gongs

- Ko Kiy: oboe, gong chimes, drum-gongs

- Pong Rean: chime of gongs, drum-gongs

- Thuom Tei: gong chimes, drum-gongs

- Horng horn: drum- gongs

Sleepy musicians can sometimes be seen in the middle of their instruments. Such a scene is not considered incongruous in Cambodia. Indeed, it recalls the mythical scene painted in almost all the pagodas of the country where are represented the musicians asleep in the middle of their instruments at the moment when the Buddha leaves his palace definitively.

But can also see the oboist making new reeds for his instrument.

Before beginning to play, the musicians perform a ceremony (sampeah kru), common among all Khmer artists, which consists in praying for the masters of music, dead and alive. The leader of the troupe light candles and burn sticks of incense. The offerings consist of a couple of bay sey pak cham, each surmounted by a candle and five sticks of incense, a couple of sla thor, a cup with raw rice, betel leaves and five candles, five sticks of incense, two bottles of water and two sodas, two bags of raw rice, a plate containing five types of offerings, each five in number: cigarettes, fragments of areca nuts, sticks of incense, rolled betel leaves, flowers and a 500 riel bill.

Throughout the week, the musicians are fed and paid by the organizing family.

Choice of the repertoire during the funeral process

The kantoam ming repertoire is limited: the Wat Svay Thom ensemble has eleven tunes for the static game and one for the processions and the Wat Trach only four. The pieces are not related to the phases of the ritual as is the case for example for weddings. The arbitrary choice lies with the oboe player.

A singer fallen from the sky

March 4, 2018 is an important date in the landscape of the revival of Cambodia's traditional music. A few weeks earlier, Cambodian Living Arts organized a meeting between a British couple and the musicians of Master Seng Norn's kantoam ming ensemble at Wat Athvear, near Siem Reap. During the exchanges that punctuated the musical pieces, the Khmer guide, who accompanied the couple, mentioned the existence of a kantoam ming ensemble with a singer in his village!

It was during a collective funeral that took place near Wat Trach, near the Angkorian temple of Chaw Srei Vibol, that we met for the first time, Pong Pon and myself, the musicians of this ensemble.

The instruments, except the oboe, belong to the Wat Trach. The ensemble consists of an oboe (sralai or pei) , a gong chime with eight gongs (kong skor), a single large gong (kong) and a drum (skor thom).

Given the particularities and uniqueness of this set, we describe below the various components.

The oboe

The oboe is made of kranhung wood. It is equipped with an eye-shaped pirouette made of red plastic.

The gong chime

The gong chime is the remnant of an instrument that has probably been coherent formerly. The first gong (the highest-pitched one) is broken but still in place. A ninth gong was tied under the second one. It's unused because also broken. However, this set can only accommodate eight gongs because the rattan frame is divided into four spaces delimited by transverse bars provided for only two gongs. This frame is painted red. The two end pieces of the frame are thin. The eighth gong (the lowest-pitched one) is damaged in its structure and doesn't sound. The fifth is an abnormally small diameter. The musician explained to us that he had recomposed the succession of gongs according to the melodies and, probably also, according to the state of the gongs.

The drum and the gong

The barrel drum is simple, without carving, except the piece of wood under the hanging ring, decorated with a lotus flower. It is painted red and rests on a bed of banana trunks.

The gong

The big gong is typical of the Thai gong style with a big central nipple surrounded by eight small ones. It is tuned to the note of the oboe which punctuates the end of the musical phrases.

Chanting

CHanting intermittently intertwines between drum and gong strikes. The melody follows the one played by the oboe and the gong chime. It would be impossible for the singer to sing constantly as he gives voice. This intermittency process allows the voice to rest. The kantoam ming plays for several hours, sometimes for several days in a row. Sometimes the singer refrains from singing to let his voice rest.

Analysis of a repertoire tune

We studied a tune played by the ensemble of Master Ling Srey (video opposite). We give you below the result of our analysis.

Instruments and sound

The music of kantoam ming is part of the cyclical conception of Khmer time inherited from India. Each instrument has a role, regardless of the Buddhist symbolism mentioned above.

- The large gong (kong chhmol), feminine, produces a sound called mung.

- The small gong (kong nhi), male, produces a sound called ming.

- The drum produces two distinct sounds: kdung or tung when one hits the skin with a stick, kroam or klok when the stick hits the drum's body.

- The kong peat produces as many distinct sounds as there are gongs, weak or strong depending on the beating power.

- The oboe (pei or sralai) plays the melody parallel to the gong chime.

The cycle

We have materialized the cycle and the strikes of the gongs and the drum on this chronogram with a counterclockwise reading, like the funeral dances, where they still exist in Cambodia.

The gongs and the drum structure the time while the gong chime, the oboe and the singer lead the melody. However, we did not wear the melody on this drawing.

The cycle is structured by the hitting of the two gongs and the drum. Each cycle is opened and closed by the simultaneous hitting of the drum's skin (kdung sound) and the large gong (mung sound); the latter also marks half of the cycle. The ming sound, depending on the case, marks three-quarters and sometimes even the first quarter of the cycle. The drum marks the first quarter (when it is not the ming sound) and other more or less precise subdivisions. The gongs hit the silence times of the gong chime. In this piece, two distinct melodies develop over two consecutive cycles, then repeat themselves.

It should be noted that the interval between the opening of the cycle and the first quarter as well as between the first half and the third quarter are empty of strikes.

The melody

The oboe and the gong chime play the same melody. However, as is the case in Khmer music in general, it is interpreted differently. The kong peat structures the time inside the cycle by marking more or less the 32 subdivisions. The oboe joins him on a few points of melodic rendezvous.

Melodic percussion music as a language element

Each instrumental melody is associated with a known or unknown song of the musicians, according to their degree of knowledge and training. To this day, there is only one singer in the Siem Reap region who knows four songs!

The words of a song are automatically associated with a melody when it is known to the listener. Thus, instrumental melodic music carries semantics that can be known, ignored or forgotten. In summary, several cases occur:

- The musician and the listener are ignorant of the words of the song underlying the melody;

- The musician knows the words of the song but the listener ignores them;

- The musician ignores the words of the song but the listener knows them;

- The musician and the listener know the words of the song underlying the melody.

A melody is not a banality since it is associated with a content. Why does a national anthem confined to its single melodic performance inspire so much respect? Precisely because the underlying semantic content must be respected. Generally, the hearing of the single melody triggers in the listener-knowing, the silent song of the words if it is not obliged to sing. On the other hand, anyone who doesn't know the lyrics will only hear a melody.

The melodies of kantoam ming (but also pin peat) carry a semantic content that could enlighten us on the origin of melodies, it is still necessary that the underlying songs are transcribed and analyzed in the light of historical knowledge, if it is. The vocabulary can also be an element of dating of the song according to whether it belongs to modern Khmer or possibly to Middle Khmer.

The safeguarding of kantoam ming by Cambodian Living Arts

In 2004, Cambodian Living Arts, based in Phnom Penh, convinced Master Seng Norn and Master Ling Srey to create a kantoam ming class in Siem Reap to save the practice and repertoire. What was done. Pong Pon, the current director of his own grandfather's troupe, Master Seng Norn, says: “We built a cottage away from the villagers' homes in the village of Trang to provide classes that took place on the evening from 7:00 pm to 9:00 or 10:00 pm (sometimes until 11:00 pm) and early morning to 4:00, 5:30 or 6:00 am. Initially, there were a lot of students. Then some have given up because this music is not especially happy! Six students and I continued and after four to five months of learning we were able to play. Our first performance took place at Wat Svay, near Siem Reap. We carried our musical instruments on our bikes! At that time, we had no experience. We only knew how to play. We had funeral benefits to be insured once a month or every other month. We worked to perfect ourselves until 2006. We participated in a festival at Vat Bo, then at Battambang, organized by Cambodian Living Arts. Since then, we continue to play at funerals.”

The repertoire of Master Seng Norn's ensemble

The repertoire referred to here is that of the ensemble attached to the Vat Svay Thom located about fifteen kilometers from Siem Reap along the RN6. The ensemble was founded in 2004 by Master Seng Norn with the support of Cambodian Living Arts.

The entire repertoire of the troupe (11 plays played statically at the funeral) was played on November 3, 2017 by three young musicians trained by the Master, recorded and filmed.

The musicians: Pong Pon (direction and sralai), Pong Rean (kong and skor thom), Tiem Tai (kong peat). Each of these pieces is available by simple click.

We have compared, available plays played in funeral situation.

Funeral situation

- Buat sva bar pul

- Buat mahori (sat mahori)

- Buat trapeang peay

- Buat krasang tiep

- Buat ale

- Buat bampe

- Buat prei ae koet

- Buat om tuk

- Buat kompao

- Buat sasar kanlaong

- Buat sampong

How do musicians think about their music?

According to Pong Pon, it is always the oboe player who has the initiative to choose and start each piece. The gong chime player follows the oboe. The oboist tries to create a stylistic playing with various devices like modifying the speed of execution. As for the gong and drum player, he doesn't count the times of the cycle, but is identified with the melody played by the oboe to strike his instruments.

As the songs are long forgotten, the musicians have only the melody as a reference.

Appease the dead

For Pong Pon, these pieces are a kind of lullabies for the dead. The piece buat bampe could also be translated as "lullaby". As for buat mahori, it also belongs to the eponymous repertoire of mahorī. This musical genre, originally a form of courtly entertainment, consists of "calming the heart and soul". Saveros Pou, in the "Cahiers d'études franco-cambodgiens N°5 de juillet 1995" specifies the meaning of the verb paṃbe and its relation to mahorī music.

"To fully grasp the meaning of this music (mahorī), one must go back even further, to the initial concept contained in the verb baṃbe which French authors used to render by "bercer". However, such a translation, without being erroneous, was a trap in itself, because it immediately evoked the world of newborns for whom so-called "lullabies" songs are intended. Moreover, the French word bercer has as its primary meaning the fact of "rocking" gently, which is not implied in the Khmer verb. Paṃbe is of obscure formation and structure, while its meaning is clear and unequivocal, namely "to soften, to soften by means of sounds", and to a lesser degree by gestures. Its object does not consist exclusively of small children, it encompasses all beings with perception and sensitivity, thus in Khmer culture humans and elephants. Paṃbe consists initially in calming the senses - which can be glossed over by "nerves" in the modern context -, which is why I prefer the term relax. In this way, paṃbe is used to calm and sedate toddlers, as well as elephants captured during the training process, in a way to urbanize them. The Khmer community has developed the scope of this verb, on the one hand by extending its use to adults, and on the other hand by passing on sensory faculties to the heart, and finally to the soul. Mahorī is aimed at adults gifted with sensitivity, reflection and even intellect, and who are looking for relaxation." (Original in French. Our translation.)

So it seems that to living humans and elephants can be added the dead.

A twelve gong's chime

Master Seng Norn was born in 1942. He started learning kantoam ming at the age of 16 from his father and uncle. His ensemble consisted of a kong peat with 12 gongs that we found.

Gong chime with nine gongs are visible on the 19th century's bas-reliefs of the northern gallery of the Angkor Wat temple. Today, they are played by the three ensembles of the Siem Reap area. However, Pon Pong, now the leader of the troupe founded by his grandfather, Master Seng Norn, had reported to me for a few months, the existence of a series of twelve gongs that was, before the Khmer Rouge revolution, a kong skor. His grandfather had played as an oboist in the kantoam ming ensemble, which included this instrument. The current owner of these gongs lives not far from the temples of Roluos. On March 4, 2018, we were able to meet her, photograph and ring these gongs.

At first glance, the set consists of two types of gongs: a group of six, with a narrow nipple, looking older, made by the same foundry and another group, at the nipple wider, more recent. But if we look closer, this last group seems itself subdivided.

Most gongs lost the wax and lead charge that allowed them to be tuned. Also it is impossible to get an idea of the range produced and their order on the rattan frame.

One of the gongs of the second group has a beautiful and deep inscription in pali. According to Trent Walker (translation), it could date from the beginning of the 20th or the 19th century, or even earlier. This is a monastic title that has become obsolete, probably since the middle of the 19th century. The inscription is no longer perfectly clear, but it seems to be written: “អ្នកសម្តេចព្រះសិតវង្សា” is either Anak Samtec Braḥ Sitavaṅsā or Neak Samdech Preah Setavongsa.

Another gong has the own name of the owner of all gongs, father of the current owner: ដៀម Ṭiem (Diem). According to Trent Walker (translation), it could date from the mid-20th century.

Another one, an inscription on all the circumference, but it is impossible to decipher it considering the small thickness of the engraving.

The owner explained to us that during the revolution, the gongs had been separated from their frame to be carried away in a bag carried on the shoulder, like a family treasure; two skor samphor drums were placed in an ox cart during their exodus. The gongs, despite their heavy weight, were not placed in the cart so they did not ring and did not attract the attention of the Khmer Rouge soldiers.

A vocational crisis

The kantoam ming is experiencing a serious vocational crisis. Indeed, the subject of funerals is not very attractive for the youth of the 21st century. In 2004, when Cambodian Living Arts came to the rescue of this art, several students had apparently given up for this reason. Moreover, the current ensemble don't promote, it's why the contracts are rare; so this situation encourages musicians to have another professional activity. Then, because of this professional commitment, they cannot accept any contract as a musician. This is why kantoam ming continues to fall apart.

News from the front

We write these lines in December 2020. The kantoam ming ensemble from Pong Pon continues to perform at funerals in Siem Reap and its surroundings. New young people have been trained and now make it possible to organize a rotation when it is necessary to play several days in a row.